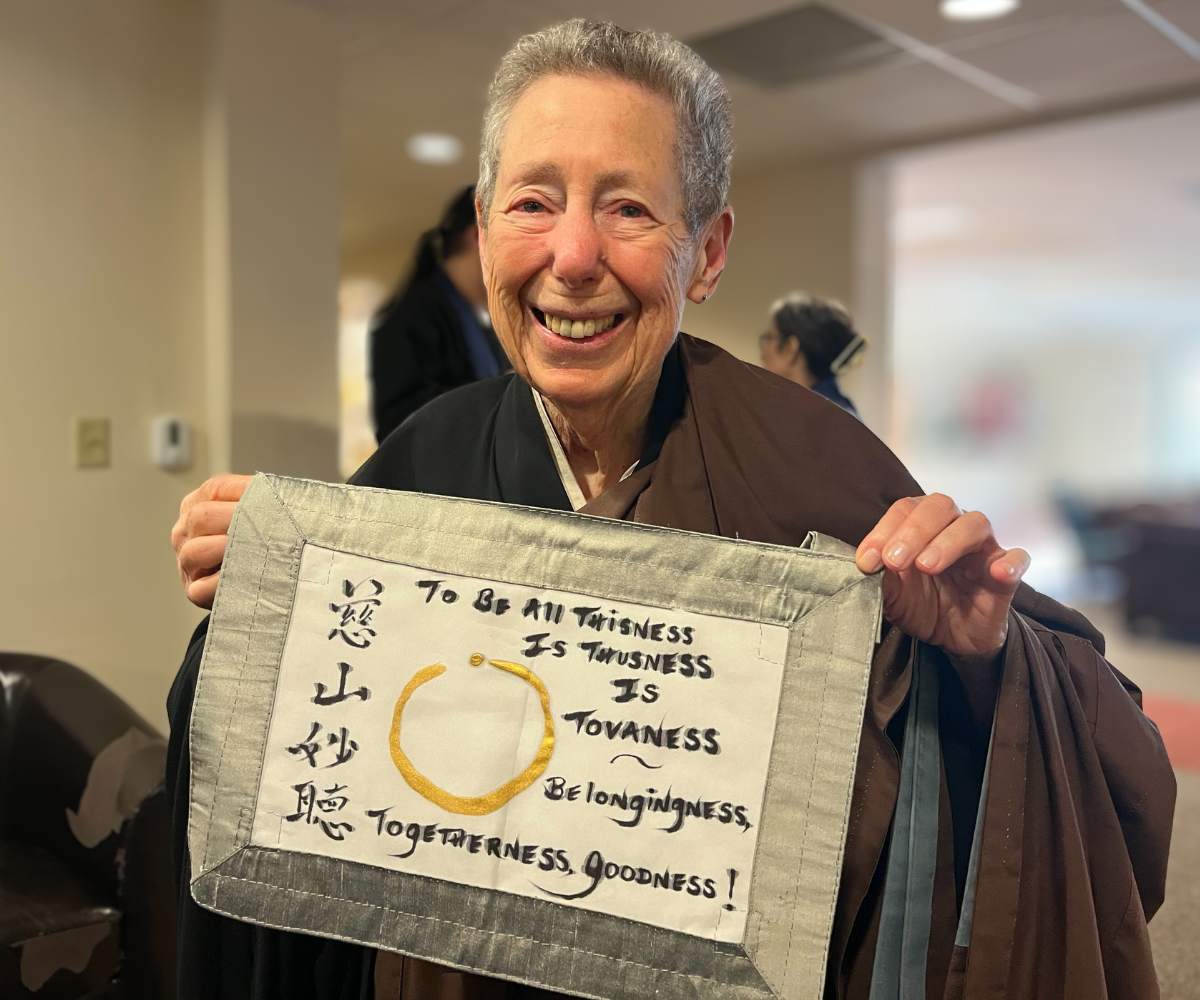

Photo by Brenda Zambrano

By Ty Greenstein

When Tova Green began writing for Sangha News Journal during the early months of the pandemic, San Francisco Zen Center, like many communities, was in a period of adaptation and improvisation. It was in that moment that Tova took on the role of blog writer, helping to document SFZC life by listening closely to the stories that were unfolding.

One of her earliest pieces, “A Mural to Greet The New Dawn”, described how a mural of poet Amanda Gorman (who recited her poem “The Hill We Climb” at President Joe Biden’s inauguration) was painted on a building at the corner of Page and Laguna Streets in San Francisco. Tova had the chance to interview and photograph the artist, Nicole Hayden, as she worked. “That was my first blog [post],” Tova recalls. “The mural was beautiful, and I really enjoyed the process.”

This combination of attentive presence and curiosity would come to define Tova’s approach to writing for Sangha News Journal. Over the next several years, she interviewed residents, teachers, staff, and sangha members, and she occasionally offered personal reflections, such as a two-part piece about her road trip to visit Branching Streams Zen centers in the Pacific Northwest. “I enjoyed the interviews themselves,” she says, “and thinking beforehand, ‘what might I want to ask this person? What might other people want to know about them?’”

Writing, for Tova, long predates her role at SFZC. She was features editor of her high school newspaper at the High School of Music and Art in New York City, wrote poetry in college, and later contributed book reviews, articles, and poems to Turning Wheel, the journal of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. In the 1990s, after moving to the Bay Area, she was part of a women’s writing group mentored by Susan Moon. That period culminated in the self-publication of chapbooks (“Zen Moments,” “Tassajara Moments,” and others) which she often gave away to friends.

Still, she notes that interviews came more easily than solitary creative writing. “Seeing a blank page can be challenging,” she says. “Doing interviews is much easier than creative writing for me.” Her method remained deliberately low-tech: handwritten notes taken during conversations, written up quickly afterward while the experience was still fresh. She valued the collaborative editing process as well—sharing drafts with interviewees, welcoming clarifications, and working closely with SFZC editors to shape flow and structure. “It feels like a collaborative process,” she says. “And when I see the final blog post with the images, it’s very satisfying.”

Among the experiences that stayed with her were interviewing Ruth Ozeki about her most recent novel, The Book of Form and Emptiness; talking to Katie Reicher, the chef at Greens Restaurant, about her first book, Seasons of Greens; and discussing “Starting and Growing a Sangha during the Pandemic” with Hakusho Ostlund, founding teacher of Brattleboro Zen Center. “Meeting someone who was a real stranger was fascinating,” she reflects. “Many of the people I’ve interviewed, I’ve known.”

Tova’s long relationship with San Francisco Zen Center began well before her writing role. She moved to the Bay Area in 1990, after more than two decades in Boston and several years in Australia, where she lived for a time on a biodynamic farm with a meditation center. When she first visited Green Gulch Farm, it reminded her of that earlier communal practice life. Soon after, she began practicing at Berkeley Zen Center as well.

In 1999, she moved into City Center as a resident. After a year and a half, she went to Tassajara, initially intending to stay for one practice period but ultimately remaining for over four years. Encouraged by her teacher Linda Ruth Cutts, she committed to five years of priest training, receiving priest ordination in 2003 and later completing her training at Green Gulch. Along the way, she worked on When Blossoms Fall, a booklet on Zen approaches to death and dying—a project that later led her to train, volunteer, and work with Zen Hospice Project.

In 1999, she moved into City Center as a resident. After a year and a half, she went to Tassajara, initially intending to stay for one practice period but ultimately remaining for over four years. Encouraged by her teacher Linda Ruth Cutts, she committed to five years of priest training, receiving priest ordination in 2003 and later completing her training at Green Gulch. Along the way, she worked on When Blossoms Fall, a booklet on Zen approaches to death and dying—a project that later led her to train, volunteer, and work with Zen Hospice Project.

For three years, Tova worked as a hospice social worker while living at City Center. “My practice helped me be fully present with other people’s fear, distress, grief, sometimes anger,” she says. She describes beginning her days in the zendo, then changing clothes and heading out to work. Teachers Paul Haller and Blanche Hartman offered practical guidance; one piece of advice that stayed with her was to park a few blocks away from a patient’s home and use the walk to breathe, ground herself, and arrive fully. Over time, she learned deeply about loss. “By the end of my three years of hospice social work, I realized I had lost 200 patients and their families,” she says. Art, music (Tova plays cello), and being in nature became essential counterbalances to grief.

In 2010, Tova co-founded the Queer Dharma affinity group at City Center, helping to create what would become a vital practice space for the LGBTQIA+ community. What began as a monthly gathering with meditation, talks, and tea quickly drew 20 to 30 people regularly. “People wanted a combination of things,” she explains. “They wanted to sit together, learn from other queer voices, and have time to socialize.” Over the years, Queer Dharma expanded to include one-day sits, Tassajara Sangha Weeks, and, during the pandemic, an online community that drew participants from across the U.S. and around the world. For many, it became a gateway into Zen practice.

As Tova steps away from her formal roles at SFZC, her legacy is not just the many positions she has held, but the way she listened to the stories of friends and strangers alike and helped them to reach the wider sangha. Through her writing, her quiet presence, and her unflagging spirit of curiosity, Tova helped the sangha see itself more clearly.

SFZC is grateful for Tova’s many years of practice and service and wishes her well in her next chapter at Enso Village!