I do not know whether it is too late to stop the mad rush toward a hotter climate … but I will continue to walk in the other direction, away from the culture of consumption and immediate gratification, away from the culture of separation and colonization, toward a life of connection with a compassionate Earth.   —Shodo Cedar Spring

Article by Myoki Stewart, SFZC resident

Photos by Compassionate Earth Walk

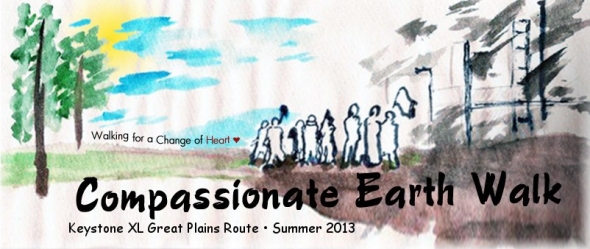

Two years ago during a practice period at Tassajara, Soto Zen priest Shodo Cedar Spring began to envision a pilgrimage—a walk along the proposed route of the Keystone XL Pipeline through the heart of North America to express her deep concern for the environment (see details on the pipeline below). Shodo reports that her root teacher, Shohaku Okumura, once said (before the walk was even imagined), “It needs to be done. Someone has to do it. And I can’t help you.†She then remarked, “That is his teaching style. He says you do what you are doing, and you be you.â€

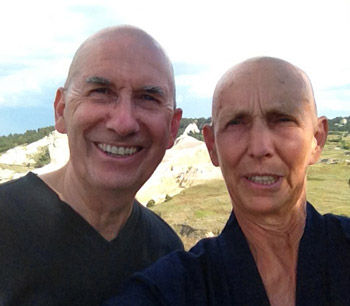

With encouragement from San Francisco Zen Center Central Abbot Myogen Steve Stücky (then at Tassajara), she spent the next two years preparing for the journey called the Compassionate Earth Walk, which began this July and is slated to end this month. Abbot Steve Stücky even joined her and her group for a few days last month.

Her courageous vision, which she refers to as a spiritual walk rather than a protest, may also happen to reflect ideas about pilgrimage held by Suzuki Roshi more than 50 years ago. One of his students, Barton Stone, embarked on a similar pilgrimage in 1960 from Union Square in San Francisco to Moscow, Russia, over concern about nuclear testing. Barton said Suzuki Roshi was “very much in favor of it … enthusiastic, even!†He recalled that later, “one day after I’d returned from the Moscow walk, Okusan [Suzuki Roshi’s wife] came to me with this newspaper clipping that showed ranks and ranks of Japanese Buddhist monks protesting nuclear weapons on Hiroshima Day in Japan. She pointed to Suzuki Roshi in the picture. She wanted me to know that he was part of that anti-nuclear march. It must have been maybe 1958 when that walk took place.â€

When asked if he had any suggestions for the Compassionate Earth Walkers, Barton Stone replied, “Hold everyone that you meet with love in your heart.â€

About the Pipeline and Its Effects

The Keystone project, which inspired Shodo to take action, would bring synthetic crude oil extracted from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, and the northern United States to refineries on the Texas coast. Proponents of the pipeline say it is safe, economically beneficial and necessary for industry. Among the top concerns of those opposed are the devastating effects of the extraction process on the surrounding land and people, and how the route cuts through wilderness, farmland, and even a major aquifer, carrying highly corrosive material.

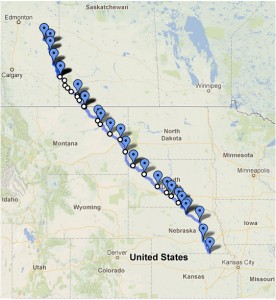

To begin, the walkers joined the Tar Sands Healing Walk in Alberta, crossed the border into Montana and have continued through South Dakota to Nebraska, where the Ogallala Aquifer is located. The significance of both the start and end points cannot be overstressed, considering these facts:

- The tar sands extraction process produces “three to four times more carbon emissions per barrel than conventional oil.†(The Guardian, May 2013).

- The Ogallala Aquifer is one of the largest underground water tables in the world (174,000 sq. miles), and at least 27% of all irrigated land in the United States relies on water from the Ogallala.

- The aquifer provides drinking water for 82% of the population living in the High Plains region (Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming and parts of Texas).

- The material (called dilbit) that would pass through the proposed 10,000 miles of pipeline is not recognized by the US government as being different from regular oil; however, dilbit is much more toxic and difficult to clean up. Furthermore, shipments of dilbit are tax exempt based on a Congressional decision from 1980 before the environmental impact of oil from sand could be fully understood.

When Shodo drove the route last year as part of her preparation, she met with many groups along the way. She was struck by the devastating impact the tar sands have had not only on the land but also on its people. She met First People who had moved away for school and returned. It was as if they “had left a dreamland filled with medicinal plants and bird songs, and came back to basically a nightmare. The tar sands are like if you take the ugliest paved strip mine and you add a lot of nasty smells to it. Traditional livelihoods are ruined, and people have to work in the tar sands or on the pipeline to survive.â€

She also reported that illnesses have resulted. In one village downstream from the tar sands, Fort Chynwhyn, the people are developing strange cancers. The deer and fish are also exhibiting huge cancerous growths, so the Native people can no longer hunt their food. There are also incidents of locals walking along the roads and being killed by the large tar sands trucks.

About Walking

Since Shodo began walking this July, her small band of activist companions have included a retired engineer from Portland, the Director of The Ojai Foundation and a contingent from Pick Up America (an organization that spent three years picking up trash across the country). Collectively the walkers are covering an average of 20 miles per day in two groups. They have a vegetable-oil-fueled bus that serves as both transportation and housing. And as traditional monks do, Shodo and her sangha rely solely on the generosity of others to fund the trip and to feed them. In each town, they connect with a local church or activist organization and hopefully receive a hot meal and some sandwiches for the following day.

Since Shodo began walking this July, her small band of activist companions have included a retired engineer from Portland, the Director of The Ojai Foundation and a contingent from Pick Up America (an organization that spent three years picking up trash across the country). Collectively the walkers are covering an average of 20 miles per day in two groups. They have a vegetable-oil-fueled bus that serves as both transportation and housing. And as traditional monks do, Shodo and her sangha rely solely on the generosity of others to fund the trip and to feed them. In each town, they connect with a local church or activist organization and hopefully receive a hot meal and some sandwiches for the following day.

The daily schedule reads like a monastic practice, with participants invited to wake at 5 a.m., with a period of meditation and encouragement to walk in silence each morning. Kinhin is much more rigorous than the 10 minutes to which most North American monks are accustomed, though—Shodo’s walking 10 miles a day!

All were thrilled when Abbot Steve Stücky joined the walk in South Dakota in early September. He offered some reflections on that trip:

I felt Shodo’s dedication and wanted to support her effort to bring a strong public focus to the tar sands and the pipeline in order to nourish seeds of awareness. I appreciate the focus on compassion as the basis for active engagement. Lately, I’ve been quoting Dogen, who quoted a Zen ancestor’s words: “The entire earth is the true human body.†Carefully attending to our true body implies that we observe how our activity as a species impacts the whole earth body. And it means that we naturally want to practice restraint … we need to understand that supporting a healthy body means that we leave much carbon (oil, coal, etc) in the ground, that we walk lightly as individuals, and that we collectively create policies to protect what we hold in common from our own greedy careless human tendencies.

I felt Shodo’s dedication and wanted to support her effort to bring a strong public focus to the tar sands and the pipeline in order to nourish seeds of awareness. I appreciate the focus on compassion as the basis for active engagement. Lately, I’ve been quoting Dogen, who quoted a Zen ancestor’s words: “The entire earth is the true human body.†Carefully attending to our true body implies that we observe how our activity as a species impacts the whole earth body. And it means that we naturally want to practice restraint … we need to understand that supporting a healthy body means that we leave much carbon (oil, coal, etc) in the ground, that we walk lightly as individuals, and that we collectively create policies to protect what we hold in common from our own greedy careless human tendencies.

I was able to join the Compassionate Earth Walk for four footsore happy days mindfully walking the bright, windy, vast rangeland in South Dakota. We passed the (Jizo) bodhisattva staff from team to team and entered into dialog with local residents along the way. Some ranchers were very hospitable and shared concerns, opinions, food and fellowship, along with many questions. The walkers are each experiencing this as a life-changing pilgrimage and are peacefully inviting serious self-inquiry and inspiring many others along the way. Please support them and find your own way to take compassionate action!

An Interview with Shodo

From her perspective on the ground, Shodo responded to a few questions from me, summing up some of her thoughts about the difficult realities of the situation:

Myoki: Are you afraid or feel the walk is dangerous?

Shodo: There are people out there who think we don’t care about them; that we are the outsiders coming in. They want to have jobs and they want to eat, and they’ve been told the pipeline will bring them money. The people who live along the proposed pipeline route—the ranchers and farmers who are against the pipeline—are pretty lonely because they are the minority. One woman from Nebraska said she’d only walk with me if we have security. And meanwhile, the police are getting training from TransCanada on how to deal with the “ecoterrorists.†We are being careful and will not go onto private property, but stay along public roads.

Shodo: There are people out there who think we don’t care about them; that we are the outsiders coming in. They want to have jobs and they want to eat, and they’ve been told the pipeline will bring them money. The people who live along the proposed pipeline route—the ranchers and farmers who are against the pipeline—are pretty lonely because they are the minority. One woman from Nebraska said she’d only walk with me if we have security. And meanwhile, the police are getting training from TransCanada on how to deal with the “ecoterrorists.†We are being careful and will not go onto private property, but stay along public roads.

Myoki: If you could have five minutes with President Obama, what would you say?

Shodo: I would say, what are they (Big Oil and Gas) doing to make you do the opposite of what you seem to believe? You have a choice of life on the planet in the future or watching everybody—including your own kids—go through starvation, drought, floods, storms, famine, disease. It’s not like stopping the Keystone will guarantee that we don’t do those things, but allowing it to go forward—it’s almost the nail in the coffin….

Myoki: On your website you say one of the intentions of the Compassionate Earth Walk is to walk away from separation and colonization. Obviously, you consider both the tar sands and the pipeline acts of colonization, but will you say something more about your intention?

Shodo: We have been living in a kind of machine culture—somewhat disconnected from the earth and each other. We humans are always orienting somewhere else. We don’t think we are part of it. Decolonization is about becoming part of it and realizing everything is interconnected. In order for humans to survive, people have to begin to at least understand the obvious physical level of interconnection: that in fact there are consequences to our actions and that the Earth is always taking care of us. It’s still taking care of us as well as it can. I don’t take that personally … it’s just the way the world works. Decolonization is about coming home.

_____

You can continue following Shodo’s progress in these near-final days of the walk, through the posts on her website, compassionateearthwalk.org.