Al Farrow designed and constructed the bell that will be used in the ZC50 event Resounding Compassion: A Concert for Peace. The concert is on June 4 at the SF Conservatory of Music.

by Tova Green

by Tova Green

I spoke with Al Farrow in his workshop/studio in an industrial area in San Rafael. I was curious about the bell he had designed and crafted using bullets for Resounding Compassion: A Concert for Peace, one of the Zen Center 50th Anniversary events, and wondered what led him to use weapons in this and other sculptures. Farrow described his work and its meaning.

“My work is not dogmatic; it’s open to interpretation. I want it to be provocative. I used a round steel drum in the center as an image of the sun or a planet, full of energy and life. The bullets that surround it are symbols of violence. I think the element of wonder, or discovery, is important, so I hid the welding, glue and screws. When people are confronted with my work they may wonder, ‘How did he do that?'”

This is Farrow’s first bell. His friend Shinji Eshima asked him to make it for the Resounding Compassion concert. “I saw the image right away,” Farrow said. “I was very busy and thought I didn’t have time to complete it and considered having it done at a machine shop, but I realized I wanted to construct it myself. … From a distance someone seeing the bell may be drawn to it by its beauty, its structure. When they come closer they discover, ‘Oh, those are bullets.’ I aim for harmonious assemblages of materials.”

Farrow described his sculpture of a cathedral at the DeYoung museum: “Its a six-foot-long Gothic cathedral made of guns and bullets. When strangers see it they begin talking to each other and to the guards. Both people who love guns and those who hate guns like that piece.”

Farrow also sculpts mosques, synagogues, and religious objects such as menorahs (branched candle holders lit at the Jewish holiday Chanukah) that incorporate guns and bullets. One menorah is made from a machine gun used by Nazis and French pistols used by the Vichy regime that supported Hitler.

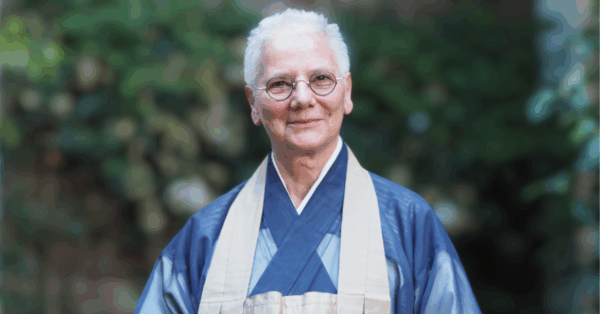

Al Farrow and the bell. Photo by Tova Green

We walked through his workshop to see two synagogues he is currently completing for a show this summer in Belgium. “I have been doing social commentary art all my life. I began the series of religious objects and buildings 17 years ago after a trip to Europe in which I saw Catholic reliquaries. I thought about all the violence done in the name of religion. This happens in all religions, even Buddhism.” Farrow intends to sculpt Hindu and Buddhist temples and is researching them now.

Born in Brooklyn in a Jewish family, Farrow rejected Judaism after his Bar Mitzvah. He appreciates religious tenets but not religious organizations. After his children were born, Farrow investigated various religions and decided not to give his children any religious education – “Most important was to raise them with respect,” he said.

Farrow showed me his early sculptures of Africans carrying bullets, his way of expressing concern about international arms sales and arming young soldiers. He also sculpted bodies fused to flying machines. In one a figure is attached to an airplane modeled after the Enola Gay that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Farrow feels that his work, especially the pieces cast in bronze, will outlive him. He sometimes thinks that, centuries from now, future generations, like archaeologists, will uncover his work. “I will be long gone, but the work will speak my mind.”

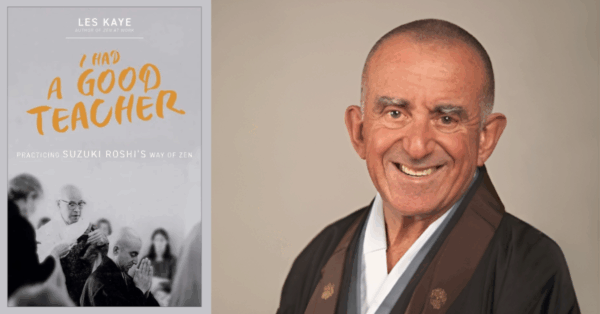

Connecting the Dots: An interview with Shinji Eshima by Tova Green