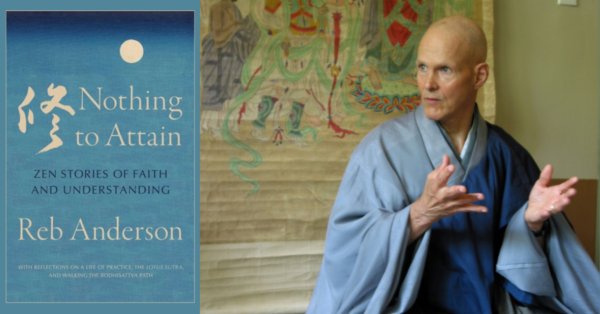

Photo by Margo Moritz

In this letter, Central Abbot Tenzen David Zimmerman writes on forgiveness and repair in his own life and how SFZC is working with former Abbot Richard Baker to reconcile a difficult past and move forward together.

Dear Sangha:

I first came to San Francisco Zen Center (City Center) in the Winter of 1991. At that time, my father was dying of cancer and I was seeking a way to reconcile our long-strained relationship. This included addressing the ways that I felt he, as a physically and emotionally abusive alcoholic, had harmed me and our family during the years we lived together.

I saw in Zen a pathway to healing, one that included learning how to become the compassionate, peaceful, trustworthy, and steadfast presence I had yearned for while growing up. In time, I was able to forgive my father and reconcile myself to the fact that he was, in his own confused way, trying to figure out how to be a human being in this challenging, samsaric world. Couldn’t the same be said about all of us?

Throughout our lives, we experience many kinds of harm from others, each affecting us in different ways. Some are minor—a casual remark from a friend that stings our pride—while others are devastating and deeply painful, such as acts of extreme violence or the loss of a human life.

Often, in order to feel that the world is safe again, we want the harm to be recognized and stopped, our pain acknowledged, an apology given, some form of repair pursued, and a promise that the wrongdoing will never happen again. When this is possible, it can be profoundly healing, even transformative. But when it’s not, we may be left feeling irreparably wounded, our trust in life and other people damaged.

In Buddhism, one of the greatest expressions of compassion is forgiveness. The root meaning of forgive comes from Old English and translates to “to give completely”. Over time, the meaning has deepened to foregoing the desire to retaliate, and thus offering a chance to reestablish mutual trust and harmony.

Forgiveness doesn’t mean forgetting the transgression; rather, it means letting go of the anger, fear, resentment, and blame we feel. Forgiveness doesn’t change what happened, but it does change our way of relating to what happened. Forgiveness also doesn’t relieve the offender of their accountability, nor does it automatically redress a wrong. Neither does forgiveness mean that we have to trust the offender not to re-offend. We can forgive an alcoholic parent or partner, but that doesn’t mean we trust them with a bottle of whisky.

However, to make forgiveness possible, we first need to genuinely acknowledge our pain. This process can’t be rushed; we need time to honor the wound and integrate its truth to lay the foundation for healing and reconciliation. Forgiveness ultimately requires that we take responsibility for our feelings rather than blaming another person. We may need support from trusted friends or skilled mentors to help us through this process.

There are also many instances when we are the ones seeking forgiveness for harm we have caused, whether inadvertently or intentionally: As our atonement chant says, “All my ancient twisted karma, from beginningless greed, hate, and delusion, I now fully avow.” Just as we can feel a great relief to forgive, so too would we like to feel the relief that can come with another’s forgiveness. We also need to be able to forgive ourselves, which requires humility, genuine remorse for our unskillful actions, and a wholehearted effort to make amends. Going forward, we refrain from repeating the behaviors that caused the harm and commit to acting in ways that acknowledge our interdependency.

Forgiveness, even self-forgiveness, is about recognizing that we are all flawed, karmically conditioned beings. We are all imperfectly perfect. I want to live in a world where I am supported in being accountable for my actions, which includes being compassionately reminded when I have caused harm. I also want to live in a world where we are not defined solely by our past mistakes, but are given the opportunity to grow, change, and prove that we can be trustworthy once more.

While this isn’t always easy, especially if the harm done has been profound, it is possible. It also requires that we let go of our rigid narratives about the other person, ourselves, or the harm done, and allow for a wider, more complex, and ever-evolving view. Regardless of whatever transgression has occurred, a Bodhisattva doesn’t lose sight of each person’s inherent Buddha Nature.

Not long ago, I received an email from a sangha member expressing upset that SFZC had chosen to feature a recent Dharma talk by Zentatsu Richard Baker, the second abbot of SFZC, in our Sangha News letter. For those unfamiliar with SFZC history, Baker Roshi had been abbot from 1971, following Suzuki Roshi’s death, until 1983, when he was required to step down following the disclosure of various improprieties. While Richard’s Dharma teachings inspired numerous students and SFZC flourished considerably under his leadership, some of Richard’s behavior deeply hurt many in the sangha, a number of whom have struggled to forgive him since he departed from SFZC over 40 years ago.

In response to the sangha member, I shared that I and other SFZC abbots have been actively working toward a healing process with Richard over the past decade or more; this process aims to support the next generation of sangha members and leaders, including the current abbots (Abbots Jiryu, Mako, and myself, as well as Richard’s Dharma heir, Nicole Baden), to move forward unburdened by ─ although not ignorant of ─ the unskillful karma of some of our Dharma elders.

Over this time, Richard has expressed regret and made sincere public and private apologies for his past harmful behavior, which have been accepted by many who were affected by his actions. Based on my experiences with him, I believe Richard genuinely feels remorseful, and shares my hope that he and the SFZC community can continue on the journey of healing and reconciliation for as long as possible.

The Buddha counseled that we should forgive someone if they confess their mistake, express remorse, and vow to refrain from it in the future. I believe that Suzuki Roshi would offer similar guidance and remind us of the value of taking responsibility for our actions and making amends where possible to restore harmony.

While some may feel a particular individual hasn’t said or done enough to repent, each of us must decide for ourselves what we need to move on. We must find our own path through forgiveness, remorse, accountability, and reconciliation. No one can dictate to us how, when, and why we take up these liberative practices─ liberative because they free us of the mental and emotional burdens that hinder our living in accord with the precepts and the flow of life.

The teachings of Buddhism encourage us to address our imperfections and the reality of harm. At the same time, they embrace the possibility for transformation through a process of forgiveness. While it’s imprudent to deny the reality of suffering and wrongdoing, we can engage with it thoughtfully and compassionately, seeking healing and repair whenever possible. In doing so, we can recognize that forgiving others and seeking forgiveness are pathways to inner freedom, growth, and wisdom. These heart-mending practices allow us to move forward in life with greater understanding, and in doing so, contribute to a more benevolent and just world.

My father died eight months after I began my Zen practice, and regrettably, before I was fully able to reconcile with him. Baker Roshi is now 89 years old and recently suffered a stroke from which he is still recovering. Time is swiftly passing, and our lives are short and precious. It’s our choice what we cling to and allow ourselves to be burdened by until our last breath. It’s also our choice what we are willing to release ─ “to give completely” ─ and thus allow space for new life and possibilities to manifest while there is still time.

Central Abbot Tenzen David Zimmerman

August 2025

City Center