By Tova Green

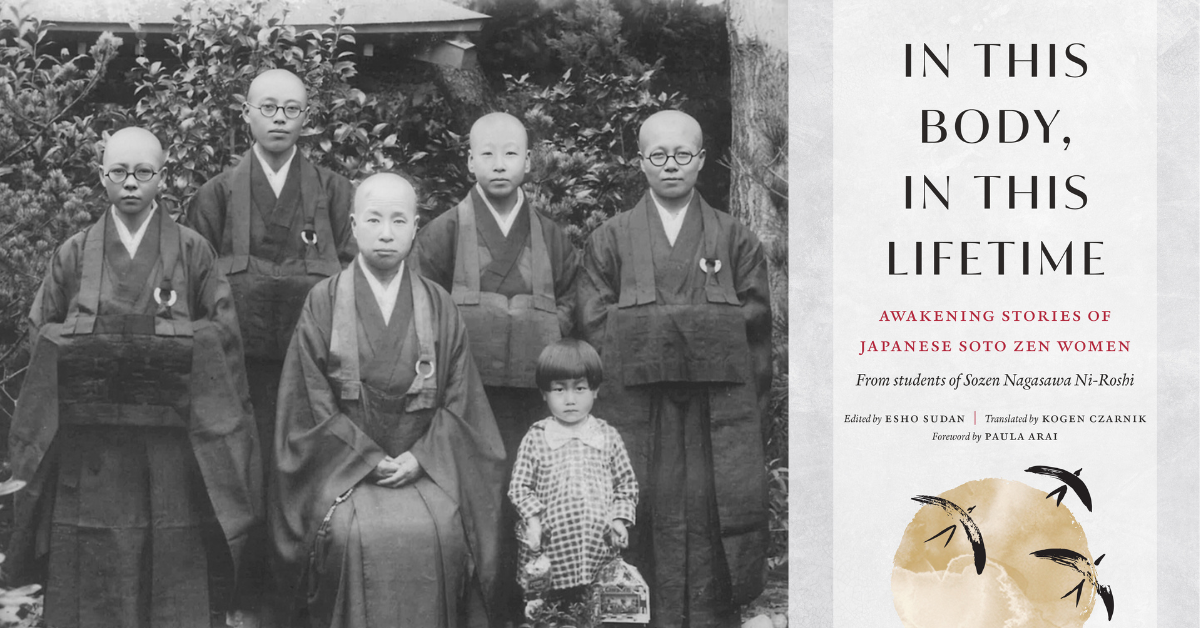

During the last several years, Esho Sudan has been editing the newly published book, In This Body In This Lifetime, Awakening Stories of Japanese Soto Zen Women, translated by Kogen Czarnik. Originally published in 1956 in Japanese under the title Collection of Experiences in Zen Practice, the book gathers writings of the awakening experiences of nuns and lay women, students of Sozen Nagasawa Ni-Roshi at Kannonji temple in Tokyo, speaking in their own words. Kogen Czarnik learned of the collection from his teacher, Tangen Harada Roshi of Bukkokuji in Fukui, and was extremely excited about it, as he knew there was very little information available about Japanese women ancestors.

Esho Sudan practices and teaches at Toshoji Senmon Sodo, the international training monastery of the Soto school in Okayama, Japan (alongside Suzuki Hoitsu Roshi, the Seido of Toshoji). Originally from Australia, she was a resident at the Sydney Zen Center, and at Zen Mountain Monastery in New York, before ordaining in Japan under Seido Suzuki Roshi in 2010. At Toshoji she teaches Baika (Zen hymn-singing), supervises translation and editing projects, and oversees international monastics practice and training.

Seven years ago, when Kogen Czarnik came to Toshoji, he shared his excitement about the book with Esho. He said he would translate a new book if Esho would edit it, and they agreed to work together. In search of a copy of Collection of Experiences in Zen Practice, they made a trip to Tokyo to visit Sozen Nagasawa Ni-Roshi’s temple Kannonji. The nun who was taking care of the temple was surprised that they knew about the temple. She had only one copy of the collection, which she gave to Kogen, along with permission to translate and publish it.

They began working on the book during Covid, when Kogen was in Poland and Esho was in Australia. Kogen later told Esho that “translating it was nightmarish and required a lot of time,” as some women were highly educated and wrote in formal Japanese and others were illiterate. Esho found that editing the text also required a lot of time.

The stories, half by nuns and half by lay women, were written during World War II and afterwards. Their temple was in Tokyo, and during the war, they could hear the bombs falling. According to Esho, Nagasawa Roshi said, “We’re just going to continue to sit.” After the war ended, the whole country was in a post-traumatic state. There was a sense of despair and a loss of faith in Japan.

“All these women, whether they came from poverty or wealth, would never have come to their experience of awakening had Sozan Nagasawa Roshi not been their teacher,” Esho said. “She was the only independently teaching woman in Japan at her time. She embodied the practice and was able to transmit it to her students. Without her example, they would not have been able to find it in themselves. She showed them what is inherent in each of us. Her training was both very rigorous and very warm. Some women only came to the temple for three to five days and had profound experiences that changed them.

“She would encourage students to come to understanding through practice. She embodied the profound truth of suchness. She was the truth to the nuns. In order for such inner change to occur, students need to have a teacher in whom they have faith, as well as the support of other students, as they go through rigorous training together.”

“She encouraged her students to develop compassion. They had very little food, yet she would give food away to the wider sangha. Thus, the nuns learned how to give.”

Esho’s experience of practicing in a Japanese nunnery in this century was very different from the experience of Sozen Nagasawa’s students. “I practiced in Japan so many years later. I’m an emancipated feminist. I felt some antagonism from some monks, but it was overridden by the belief that men and women can practice together.”

“Sozen Nagasawa Roshi was not only a formidable teacher, but was a key figure in reforming the Soto school constitution to ensure equality for nuns. Along with Kendo Kojima, who practiced at Kannonji, she made it possible for women to ordain other women, thus changing the whole landscape for nuns. She also recognized the accomplishments of lay women.

“Although the Soto constitution changed in the 1950s to allow women’s Dharma transmission, due to increasing secularization and the continuation of societal inequity for women in Japan more generally, now there are very few lay women and nuns to sustain women’s lineages.”

Esho reflected on the role of women in the history of Buddhism in Japan: “It is hard to imagine the Japan into which Buddhism first came— affirming of women, with women in positions of power and influence. The nun Zenshin was the first Japanese ordained Buddhist, creating a temple in 596 AD. Forty years later there were 569 nuns and 826 monks practicing in Japan. Now there are about 300,000 Zen monks and less than 1,000 Zen nuns—a stark contrast to those early days. The influence of Confucianism from China created many obstacles for women. Sozen Nagasawa’s time, the Meiji era, was a time of modernisation and westernization, but women were not to benefit from this until later in the 20th century. Despite this, Nagasawa Roshi and her students created a true refuge of practice and realization, from which we can still draw inspiration and encouragement today.”

Esho would like readers of In this Body In This Lifetime to come away with an understanding of the power of turning inward to find one’s inherent wisdom. She loves a verse Sozen Nagasawa Roshi included in the original edition:

Under the heavens till the end end end of all fields

Long awaited fresh breeze of the Dharma.

On June 21, Esho Sudan will be giving a Dharma talk at City Center at 10:00 am.