By Teresa Bouza

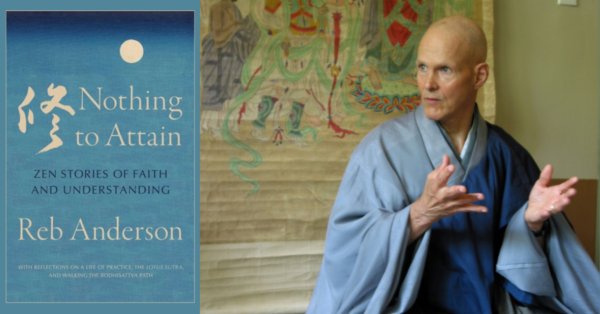

Photos within article by Barbara Wenger

Sokaku Kathie Fischer began practicing Zen in 1971 with Sojun Mel Weitsman at the Berkeley Zen Center. She was ordained a Zen priest at San Francisco Zen Center in 1980 by Zentatsu Richard Baker, and continued residential practice at SFZC for 15 more years. She received Dharma transmission from Sojun Weitsman in 2011.

A death poem by an early Buddhist nun moved Zen teacher Kathie Fischer so deeply that she has spent most of her time studying and sharing female ancestors’ stories since reading that poem two years ago. “They were strong women who kept moving forward because they were committed to practice, not because they wanted something for themselves,” said Kathie, a teacher in the Suzuki Roshi lineage. “It is important for us to know and be aware of the context for the practice of these women,” explained Kathie.

It all started with an email sent by Zen teacher Layla Smith Bockhorst notifying her students and close friends of her move to hospice after being diagnosed with cancer in 2022.

The email from Layla concluded with a verse from Bhadda Kundalakesa, a nun who lived during the time of the Buddha: “Here at the end, part of me still wants to go back and kiss every inch of every road I ever walked. But it’s enough just to say thank you—and goodbye.”

Known as Bhadda the Curly Hair, Bhadda Kundalakesa entered the most ascetic order of Jains, which required that her hair be pulled out by the roots. She eventually left the order and wandered alone for fifty years, walking barefoot and wearing her one robe.

“I still find that the poem is so moving. Such a clear and simple statement of love, gratitude, and practice. That is what got me started. Because it is from Bhadda Kundalakesa, who had a challenging life,” said Kathie, who also likes to share stories that don’t usually get told. For example, she recounts how Mahapajapati Gotami, the Buddha’s aunt and stepmother, led what is considered to be the first women’s rights march in recorded history; she and several hundred of her supporters walked more than 100 miles to the Jetavana monastery where the Buddha taught to ask for the creation of an order of nuns. The request was granted after the intercession of Ananda, one of Buddha’s main disciples and his cousin.

“Regardless of circumstance, whatever the challenges were that they met, or whatever the block, these early women teachers just kept moving forward. They were committed to practice, and they were not going to be stopped. I think women know that quality in themselves. When things are tough, we are going to walk forward in a tough situation. When things are not tough, we will keep walking forward in a not-so-tough situation. Women specialize in that.”

➢ Looking for a Different Way to Live

1982 – Leslie James Meyerhoff, unidentified, Olga Marsh, Kathy Fischer and Laura Burges

Born in Berkeley, California, in the spring of 1952 and raised in a suburb of L.A., Kathie Fischer first learned about Zen when she was 14: “Someone gave me Alan Watts’ book The Book. I read it and knew that was what I wanted.”

“The sense that this moment right now is the sacred moment, those ideas hit home for me,” remembers Kathie, who knocked on the door of Berkeley Zen Center one afternoon in 1971 when she was a 19-year-old college student. Mel Weitsman, the late Berkeley Zen Center abbot, opened the door and gave her zazen instruction. “And then, you know, I kind of never left,” said Kathie.

A child of the 60s, Kathie Fischer sees the Vietnam War as the defining moment of her life.

“My father was an aerospace engineer in LA working on the antiballistic missile program. My uncle was in the CIA and stationed in Vietnam, Japan, and Korea. My oldest uncle was a nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project with Oppenheimer, and I was a young hippie protesting the Vietnam War, which was in opposition to what my parents and their generation represented,” she explained.

The Vietnam War was a time when many young Americans learned that the government couldn’t be taken at face value. It was also a time when the role of women and many other things were questioned. “We were up for questioning in our generation,” remembers Kathie.

It was also in the 60s when the word ecology and the word environment came into consciousness: “We learned those words at that time and realized that there was a relationship between us and the natural world and the built world and that all kinds of unseen consequences would arise if we didn’t take that into account.”

Around that time, a 55-year-old Japanese Zen teacher made his dream of traveling to the United States come true. Suzuki Roshi landed in San Francisco in May of 1959. The young Americans of the time loved the practice he brought from Japan.

“One of the reasons people from my generation came to Zen centers is because we wanted to reinvent ourselves in a big way. We wanted to find a different way to live.” That search led Kathie to the zendo.

“The history of Zen is a military history. It was a practice of the samurai and so on. But I loved the practice, and I decided to think of the forms as a dance rather than a military operation. It is beautiful, people moving in unison and people chanting together. It has a feeling for me of one body,” said Kathie.

➢ A Mom at Tassajara

Norman and Kathie

Kathie met Norman while attending college in Berkeley, and soon after graduation, they moved to Tassajara and Kathie became pregnant with twins.

Suzuki Roshi’s successor, Richard Baker, envisioned and supported having families in Tassajara. To allow parents with babies and young children to sit in the zendo during the practice period, Richard Baker invented a daycare system and a task called “child watch.”

“Everybody in the practice period had to take a turn, whether they were a parent or not. One person would walk around Tassajara and listen around all the houses where there were babies. And if a baby woke up, that person would go into the zendo, tap the parent’s shoulder, and have them come. Every period of zazen, somebody walked around listening for babies. Isn’t that sweet?” remembered Kathie.

That idea made it possible for everyone to sit.

The parents also received advice about how to set up a daycare system at Tassajara from Joanna McClure, the late poet Michael McClure’s first wife, who was the head of a daycare system in San Francisco. She advised families at Tassajara about how to set up a play yard, how to relate to each other, and how to support each other.

“Richard Baker came through as a visionary who was supportive of creating a community that didn’t exist before,” mentioned Kathie.

➢ The Richard Baker Shock

Kathie was ordained a Zen priest at the San Francisco Zen Center in 1980 by Richard Baker, her teacher.

In 1984, Richard Baker stepped down as abbot of SFZC in what is known in Zen circles as “the Apocalypse,” a scandal that involved sexual affairs and abuse of authority.

“I was completely clueless until the whole thing exploded, and it was a shock. It was like I woke up from a spell. It was a total shock for the whole organization. As somebody said, it was a 500-person divorce. Things got rough there for a couple of months. After a while, I started to feel like this was going to change my relationship with Zen Center and with Richard Baker, but I cannot deny how much he helped me. I still feel that way. He is a very good teacher, and he is very clear about explaining certain things and bringing things up. And I thought, well, I just learned a lot from that man. And I will always be grateful to him. I ended up feeling I didn’t need to wipe him out of my life. Norman and I have stayed friends with him. He is older than I am. He is from an older generation, and he certainly embodies many of the blind spots of the generation and the men of that generation. I was able to forgive him and discover my boundaries. I did not continue as his student, but I feel that he is a friend and somebody I am grateful for.”

Kathie Fischer received Dharma transmission from Sojun Mel Weitsman in 2011, during her 28-year career as a science school teacher in Mill Valley.

The other teacher who was very dear to her was Maureen Stewart Roshi, who became president and spiritual director of the Cambridge Buddhist Association in 1979. She died of cancer in 1990, so Kathie only knew her for a few years.

“Baker asked all the women not to dress glamorously. We didn’t have to shave our heads, but we had to have short hair and no makeup. We were supposed to wear only certain colors. We were supposed to look like, you know, sexless creatures walking around. And here comes Maureen Stewart Roshi, who had been a concert pianist in her youth. She had makeup and perfume, and her hair was done. And she was as big as life and affectionate and feminine. And with a big personality, very, very strong, very generous. I did not know that this could exist. So she was really important to me for that reason,” said Kathie.

➢ Passing the Practice Forward

After more than 50 years of practice, the main question in Kathie Fischer’s mind is how to pass the practice forward: “I think about that a lot. It is time to think about passing it forward. So what is this precious gift that I have to pass forward?”

Unlike when she was young, the number of people who go to residential practice places is now pretty small. For Kathie Fischer, that means that for the practice to really become embedded in people’s lives, there needs to be a variety of ways for people to come together and contact each other.

She considers live streaming the “great gift” of the pandemic: “Getting together on Zoom has solved a lot of problems for people who longed to practice but couldn’t possibly get to a practice center. So people who are elderly, people who are extremely busy, people who have some health or life limitation of any kind now have access. It’s opened up doors for people. And that means that people are practicing in their own lives, in their own homes.”

She is grateful for a practice that has helped her to make the body her home.

“We are a dynamic organism. There is no such thing as staying anywhere. But there is returning. The heartbeat returns, the breath returns. And so our attention can return to the body over and over again. What I mean by staying in the body is very specific: staying in or returning to the deep sensation of breathing, of having a heart that beats. My heart beats for me whether I ask it to or not. That’s amazing.”

Kathie, Norman, and their two sons