Photo by Sara Tashker

By Tova Green

Jiryu Rutschman-Byler was born in Argentina to children of Mennonite missionaries. When he was three, his family moved to Albuquerque, NM, and then to Chicago. His parents converted to the Quaker religion and both of them have been and still are engaged in activism—his mother with Amnesty International and his father with various causes including the Sanctuary movement.

Jiryu attended Deep Springs College in Bishop, CA, for a year and a half. The college was very small (only 24 students) and had a monastic feel. He became friends with a classmate, Aaron Fischer, the son of Norman and Kathie Fischer. They went on a road trip and stayed at Aaron’s house in Muir Beach, close to Green Gulch Farm. Jiryu asked to join zazen at Green Gulch Farm and spent a night in Norman’s study, which was full of Buddhist books. He followed Norman to the zendo early the next morning.

Later, after Jiryu had left college and was living in San Francisco, he was drawn to spirituality in the form of neopaganism in an unsupervised way which, he said, was not so good for him. He was “up on a cosmic plane, becoming more distanced and less and less on the planet.” He realized he was caught up and needed a teacher and a community. At that point, Jiryu remembered the strong experience he had had at Green Gulch Farm. He learned about City Center and went there for a few weeks as a guest student. At the end of his stay he sat Rohatsu sesshin. “I was hooked.”

In the summer of 1997 Jiryu went to Tassajara, and for several years he alternated practicing at Tassajara and Green Gulch Farm. Jiryu met his first teacher, Seido Lee de Barros, at Tassajara. He received lay ordination (jukai) and his Dharma name, JiRyu FuGan – Compassion Dragon / All-embracing Vow, from Seido in 1999 and was ordained as a priest by him in 2002.

After his ordination, Jiryu went to Japan for a year and a half and practiced at Bukkokuji and Hokyoji temples. “I was moved to be doing what felt like a very ancient and authentic practice.” He wrote Two Shores of Zen, An American Monk’s Japan, based on this experience.

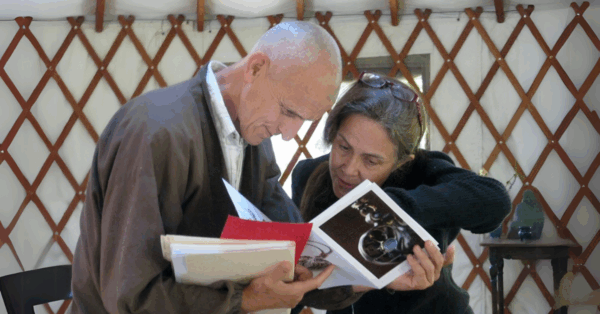

Sara, Jiryu, and their sons

Jiryu left Japan, realizing that “there were other parts of my life that needed tending.” He didn’t expect to return to SFZC because it seemed so different from what he had experienced in Japan. However, after a period of traveling and writing, he spent a few weeks at Green Gulch Farm and met Sara Tashker for the second time. They fell in love. She wanted to stay at SFZC; he knew he wanted to be with her. He felt divided—part of him knew it would be hard for him to be at SFZC and part of him knew it would be good for him to be there. They decided to go to Tassajara, then returned to Green Gulch Farm where they married, and decided to live there. Since then, they’ve had two children and are raising them at Green Gulch. Jiryu says, “Every day my family helps me to keep tending all of those parts of my life that need tending, shows me my shortcomings, encourages me to practice more fully, and most basically supports me with the kind of unconditional love that really is the heart of our practice.”

“Residential practice at SFZC has met me in different stages of my life—as a young monk, when I wanted to study, as I moved into teaching, as I moved into having a family. I am not such a disciplined person. I am gratified by supporting people and being supported by them. When there’s a schedule, I can follow it. I need that support.

“Though I have felt met in different stages of my life by the practice and teachers at SFZC, I feel we as SFZC have to do better at extending that to everyone—meeting and supporting everyone where they are as a person and in their practice. Almost from the beginning in our paths as SFZC residents we’re practicing our own practice and supporting others through that. It grows and grows. We learn to support others’ practice, both meditation and work practice, and that becomes our practice.”

During his years at SFZC, Jiryu returned to college, first to complete his BA degree and then for a master’s degree in Buddhist studies. He also self-published two books and is working on two more, has been engaged in prison work at San Quentin, and has been the guiding teacher of a Zen Center in Medellin, Colombia.

It was when Jiryu was asked to be shuso (head student) that he felt he should get more involved with Buddhist study. He enrolled in the MA Program at UC Berkeley with the group on Buddhist Studies. He appreciates the tradition, the Japanese language teaching, and scholarship. “It’s important to continue to look toward our Japanese counterparts and American scholars who devote their lives to the Dharma with appreciation and respect. They know so much about our tradition, liturgy, philosophy, and history.” The title of Jiryu’s master’s thesis is “Soto Zen in Meiji Japan—The Life and Times of Nishiari Bokusan.”

Sojun Weitsman invited Jiryu to work on some unpublished Suzuki Roshi manuscripts. They worked together on this project for two or three years, until Sojun’s death in January 2021. Jiryu feels that Sojun wanted him to understand Suzuki Roshi’s teachings so he could continue the work of editing. Two books are in process. The first, with one section on Zen practice generally and another section on Bodhisattva Precepts, has a working title, Becoming Yourself. The second, with a working title of Things As It Is, is a compilation of many of Suzuki Roshi’s comments on koans. Jiryu hopes that both books will be published over the next few years.

The Buddhadharma Sangha at San Quentin prison started in 1999 after some people incarcerated there reached out for a Buddhist teacher. Seido Lee de Barros, who was living at GGF, responded and began going there weekly. The Buddhadharma Sangha consists of incarcerated people and so-called “free people” practicing together, side by side, to support and be supported by one another. As Seido’s student, Jiryu accompanied him to San Quentin and helped however he could. When Seido retired, Jiryu assumed the role of teacher for the Buddhadharma Sangha. Over the years, over forty members of the Sangha have received jukai at San Quentin. There have been shuso ceremonies and one-day sittings. Jiryu is amazed by the sincerity and depth of the incarcerated practitioners’ practice in the dehumanizing prison environment under terrible, sometimes hopeless, circumstances. He is no longer active in the Buddhadharma Sangha and is grateful to those who are leading it now and helping it to thrive.

Jiryu began an ongoing connection with the Zen Center Montaña de Silencio in Medellin, Colombia after Sanriki Jaramillo, the leader of Montaña de Silencio, who felt a deep kinship with Suzuki Roshi and his lineage, reached out to SFZC to connect him with a teacher. Sanriki wanted his sangha to be affiliated with Branching Streams, the network of Zen Centers and sanghas in the Suzuki Roshi lineage. Steve Weintraub, the Branching Streams liaison at the time, thought of Jiryu, and organized a meeting with Sanriki in San Francisco. Sanriki and Jiryu realized they had a surprising connection: Jiryu’s father had been born in a small town in Colombia that had had a Zen training temple which was the temple in which Sanriki had trained. Jiryu has been going to Medellin once a year to lead sesshins. He ordained Sanriki as a priest in the Suzuki Roshi lineage, and plans to give him Dharma transmission this fall.

Jiryu is grateful to his many teachers over the years, and especially feels indebted to his late formal Zen teachers: his jukai and priest ordination teacher Seido Lee de Barros, his teacher in Japan Harada Tangen Roshi, his shuso teacher Myogen Steve Stücky, and his Dharma Transmission, root teacher Sojun Mel Weitsman.

As he prepares to become the next Green Gulch Farm Abiding Abbot, Jiryu sees himself as part of the mandala of everyone supporting everyone. “It calls on my utmost sincerity and vulnerability in order to do something together. That’s the only way for Zen practice to be meaningful. That includes what Suzuki Roshi spoke of as ‘sharing our feeling’ with one another. To do this role I need people to hold me accountable, give me feedback. My vow is to do my best to receive that with an open heart and mind, and to keep growing.”