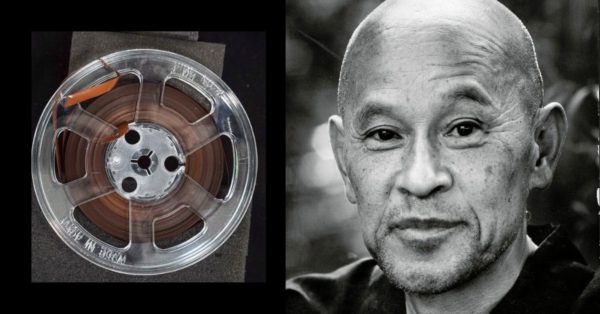

To listen to this talk, “Genjo Koan no. 2,” see the Suzuki Roshi Audio Archive where it is listed on the right side.

This talk was given by Suzuki Roshi at Tassajara on August 21, 1967.

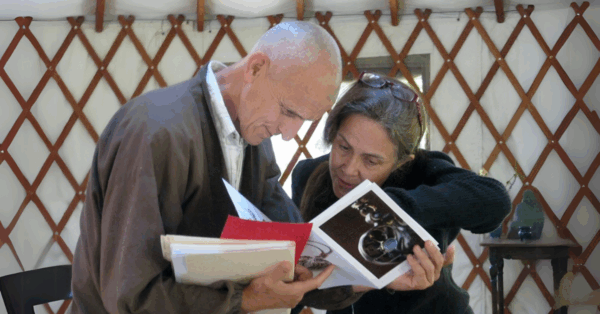

Description:

Construction at Tassajara with Suzuki Roshi at lower left

This third talk from the historic inaugural sesshin at Tassajara in 1967, given the day after the first two (tapes 14 and 15), is divided into two parts, held together by the unspoken theme of the “dharma position” (ho-i in Japanese).

In the first half, Suzuki Roshi is expounding on the notion of work-practice. This is exemplified in Dogen’s Tenzo Kyokun, and Suzuki Roshi tells one of the pivotal stories from that text, about the young Dogen’s encounter with an experienced tenzo who tells him that he cannot abrogate his responsibilities, even to spend one night away from his monastery. Suzuki Roshi encourages his students to do their very best at whatever work position they are given, without being attached to the results: “You should not take pride in your ability. Forgetting all about your ability and result of effort, you should still make your best in your work. This is how you work in a monastery as a part of practice.” (1:23)

This is also tied in with the understanding that in the future they will have another position: “So today we have today’s work, tomorrow we have tomorrow’s work, and each one of us has his own work, which should be perfect.” (9:21) Undertaken in this way, work becomes a practice that enables the monastery to flourish, even though we are not focused on the outcome of our work. He continues, “Of course, if you visit good monastery, everything is in order, and everything is—vegetables is growing healthy and plants are—are healthy, and everywhere is clean. And tools and everything is well polished and sharp. That kind of monastery sure to be a good monastery.” (14:08)

Suzuki Roshi then pivots to the “firewood and ash” section of “Genjo Koan” to underline how we need to be fully in the present without imagining some future result or future condition. If we practice guided by the expectation of, or wish for, enlightenment, we lose the value of the present moment. If we remain in the understanding of Dogen’s “practice-enlightenment,” our continuous practice through all aspects of monastic life enables us to experience the unbounded nature of the present moment.

He comments further on the following paragraphs of the “Genjo Koan,” including the famous “moon in a dewdrop” passage with the tart observation, “This kind of understanding is beyond our thinking. You can explain it in our logic, but you cannot, the explanation will not be perfect.” (26:00) He encourages his students to simply continue their practice, without comparisons or being caught by ideas, just seeing what is around them, just doing what is needed. As he had discussed the day before, if we have some kind of enlightenment experience, that is not the end point of our practice, “Enlightenment after enlightenment we should practice our way.” (30:15)

The fruit of this kind of practice is that the state of mind which monastic life is especially designed to cultivate can be experienced anywhere: “The monastery is not some particular place. Whether you can make Tassajara a monastery or not is up to you. It may be worse than city life even though you are in Tassajara. But when you have wisdom of Prajnaparamita Sutra, even though you are in San Francisco, that is a perfect monastery. This point should be, you know, fully understood.” (36:44)

Generations of Tassajara students have been able to discover this for themselves, thanks to the guidance of Suzuki Roshi and his successors.

- To view all of the talks that have currently been released and to learn more about this project, see the Suzuki Roshi Audio Archive.

- Please donate to the preservation of San Francisco Zen Center’s audio archives.

- Non-monetary support is also welcome. This collection of talks is a living, evolving archive that depends on input from people like you to unlock the wisdom it contains. Several of the newly discovered talks are in need of transcription, and nearly all can benefit from listeners adding descriptions and keyword tags to improve searchability. To get started, visit the Suzuki Roshi Audio Archive page for many ways to engage.