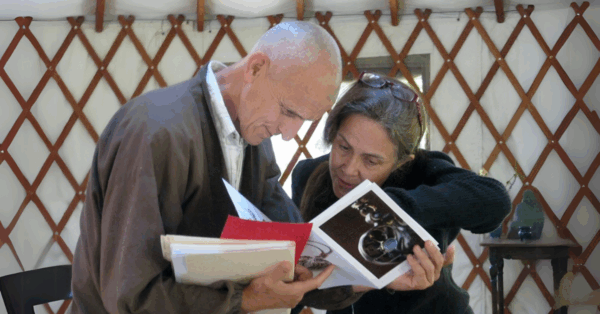

Thich Nhat Hanh striking the Peace Bell at City Center during a visit in 2013. Photo by Shundo David Haye.

When San Francisco Zen Center received the news of the passing of Thich Nhat Hanh, all three centers—Green Gulch Farm, City Center, and Tassajara—initiated the ringing of 108 bells that is the traditional form for acknowledging the death of teachers, other significant figures, and sangha members. Each center also conducted a memorial service. Thich Nhat Hanh was a friend of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi and visited San Francisco Zen Center a number of times over the years. There is a full tribute and memorial page on the Plum Village website.

By Ryuko Laura Burges

If we are peaceful, if we are happy,

we can blossom like a flower

and everyone in our family,

our entire society,

will benefit from our peace.

Thich Nhat Hanh / October 11, 1926 – January 22, 2022

Our great friend and teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, has entered the Great Mystery. The New York Times shares this news: “One of the great Buddhist teachers of our time, Thich Nhat Hanh, died today at Tu Hieu Pagoda in Vietnam, the Buddhist temple where he was ordained at age sixteen. Following his stroke in 2014, he had expressed a desire to return to his homeland, and, in October 2018, moved back to his home temple. There, he spent the last years of his life surrounded by his close disciples and students.” He was 95 years old.

Thay, as he was affectionately known, was one of the world’s great Bodhisattvas, bringing Buddhism to the West with his compassionate teachings. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1967, referring to Thay as “an apostle for peace and non-violence.” Dr. King said, “I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of this prize than this gentle monk from Vietnam. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.”

Born in Vietnam in 1926, Thay became a novice monk at Tu Hieu Temple, in Hue City, at the age of 16. Later, he protested the Vietnam War, dividing his time between the temple and giving aid to those suffering from the bombings and strife that plagued war-torn Vietnam. Because of his efforts toward peace, he was exiled from his country.

Relocating to southern France, Thay and fellow monastic Chan Khong founded Plum Village in 1982 as a monastery and practice center, offering retreats and teachings to his students and to visitors from all over the world. Thay traveled from there to teach in many countries. He coined the term we all know today, “engaged Buddhism,” encouraging those of us who follow the way of the Buddha to act as citizens of the world, for the benefit of all beings. His more than 100 books have made Buddhist teachings accessible to millions and have been translated into many languages.

On November 11, 2014, Thay suffered a severe stroke. He had a slow but steady recovery, though never fully regaining the ability to speak. He was able to return to his root temple in Vietnam, where he was cared for by the monks and nuns and the medical team that attended him there.

For many years, Thay had been a great friend of San Francisco Zen Center, helping us and teaching us in times of harmony and in times of disruption and doubt. During his visits to SF Zen Center over the years, I remember him suggesting that we smile more and get more sleep—perhaps those two things are related? I’d like to share a few quick brush strokes in honor of the long-term friendship between Thay and SF Zen Center.

Reverend Shosan Victoria Austin remembers being a student during a practice period at Tassajara in 1982 when Thay arrived, along with Robert Aitken Roshi and others, to lead a Peace Conference for Buddhist teachers. Thay offered a two-week class to the students there to explore the practice of writing gathas, short phrases composed to bring our attention to the present moment, no matter what we might be doing. He also offered a daily lecture on form and emptiness.

Rob Lee was there for practice period and acted as a volunteer when Thay requested one. Thay asked him, “How old is your hand?” Rob replied, “32?” Thay responded, “Can you see your mother’s hand in your hand? Can you see your grandmother’s? Can you see the food and water that you’ve taken into your body? Now, again, how old is your hand?” “I don’t know,” Rob answered. Witnessing this exchange presented Victoria with a koan that stayed with her for a long time.

Victoria had a cold during the conference, and she tried to stay in the back of the class so that she wouldn’t disturb or infect anyone. She went back to her cabin to take care of herself, to take a nap and rest. She heard a gentle knock at the door. Thay stood there smiling and offering her a bottle of Vitamin C.

When our community split open around that time, Thay and Victoria spoke about the importance of not losing faith in our practice, even in the midst of doubt about the student/teacher relationship. He encouraged us not to lose our sense of direction and to always have faith in the possibility of realizing emptiness, wisdom, and compassion in the midst of impermanence and suffering. Victoria says that just his way of holding up a leaf, just the way he walked, is an invitation to practice.

I was lucky enough to be with Thay and his sangha at Plum Village in 1990. My daughter Nova was 11 at the time and she and the many other children there were drawn to Thay and his peaceful and playful presence. We were instructed to walk slowly through the fields of sunflowers nearby and, in the evening, we gathered for a vegetarian dinner in a huge tent. I remember being impressed with how the Vietnamese children were able to sit so quietly while waiting for hundreds of people to get their food and be seated so that we could all chant and eat together. Lecturing one day in English, the next in French, and the next in Vietnamese, with headphones provided to practitioners for simultaneous translation, day after day, Thay spoke of the dharma in his soft and lulling voice. While the children spoke different languages, they found a way to play happily together, as did the adults who came from all over the world to be with Thay.

Dennis Sarni, who received jukai with Tenshin Reb Anderson at Green Gulch Farm, traveled to Vietnam in May 2019 to visit Thay at his temple during Thay’s recovery. He shared this with me: “While I fervently wanted to see him and sit in his presence, that never came to pass. I sat and mindfully walked with the nuns, ate with the Sangha and they sang a song for me. The experience felt very ethereal and mystic. Walking around his temple, waiting to catch a glimpse of him, as I avoided being bitten by a pack of temple-dogs, I did feel that he touched me. I was penetrated and changed by the power of his presence. I know I will never meet him, but in some ways, I feel I have been with him.”

Thay’s gentle teachings and persistent presence remind me of the way that water, over time, can wear down solid rock. Innumerable beings have been touched and changed by his devotion to the Dharma. May his penetrating call to peace and mindfulness echo through this world and help draw us all together at a time when global unity and awakening couldn’t be more important.

Breathing in, I calm my body,

Breathing out, I smile.

Dwelling in the present moment,

I know this is a wonderful moment.

Ryuko Laura Burges is a lay entrusted Dharma teacher in the Soto Zen tradition and a teacher at San Francisco Zen Center.

ADDENDUM, February 2, 2022

After reading this article, Rob Lee contacted Sangha News Journal to share the journal entry that he wrote just after his encounter with Thich Nhat Han.

Thank you for your lovely article about Thich Nhat Hanh. He was truly a giant. I was more than a little surprised to see my name in the article. As the encounter with Thich Nhat Hanh was deeply moving for me, I wrote exactly what was said in my journal shortly after the meeting, the entry dated March 16, 1982, which I still have. It’s rather different from the story in the article. I’d appreciate it if you could clarify this in your publication.

With a deep bow,

Rob Lee

All the students of the monastery, and a number of Zen Center’s most senior people had assembled in the Tassajara dining room. Thich Nhat Hanh entered in his super slow, contemplative way, then asked for a volunteer. There was a pregnant pause. I raised my hand. He sat me in a chair facing the community, his hand very lightly on my shoulder.

“Are you alright?”

“I think so.”

“Are you sitting under the Bodhi tree?” I didn’t say anything, as it struck me as too large an affirmation to make. His hand on my shoulder was very soothing.

“I would like you to look at your hand.” I began to raise my right hand. “Your left hand …” I looked at my left hand. “How long has that hand been around?”

“Thirty-two years,” I paused, and then, “About ten seconds.”

“Does anyone else know how long their hand has been around?”

Student A explained the hand appeared each time we become conscious of it. Student B said, “I don’t know how long my hand has been around.”

Thich Nhat hanh turned to me, “Can you see your mother and father in your hand?”

I gazed at my hand, “No.”

“Anyone else?”

Student C: “I can see my parents in my hand.” Student D: “I can feel them, but I can’t see them.”

“Can you visualize their faces, bodies?” Pause. “Can you see your children in your hand? How long has your hand existed?”

“Yes,” I said, then, “My hand has always existed and it will always exist.”

What made this moment so wonderful for me was the serenity of his hand on my shoulder, how helpful all his gentle coaching, the answer issuing suddenly from something large, not me.