I am writing to honor Thomas Cleary after his passing away June 20 and his amazing legacy of translations, Buddhist and otherwise. Many of his texts are crucial to Soto Zen practice, and for all modern Buddhist practitioners. His translations are lucid, creative, and accessible. They included not only Chinese, Japanese, and Sanskrit Buddhist texts, but important Taoist and other Chinese classics. He later also translated from Arabic the Qu’ran and illuminating Sufi material, as well as translations from Greek and old Irish classics. His gift with languages was phenomenal.

I was privileged to study academically with Dr. Cleary for a year, 1986-87, including three courses, in Zen, Taoism, and Huayan Buddhism. His classes led to my studying for a Masters Degree at California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) in San Francisco, where I enrolled initially for the opportunity to study with him. He was an insightful, brilliant lecturer. In the first class in his Zen course he said that the aim of learning Buddhism is to learn about learning, and to maximize receptivity to reality although no complete formulation of reality is possible. I enjoyed several lengthy individual conversations with Cleary while walking from CIIS, back then in the Haight-Ashbury, to the Civic Center BART, where he took the train back to his East Bay home. During this year Cleary also taught two very popular classes at San Francisco Zen Center, which I also attended.

Any account of Cleary’s translations must commence with his monumental rendition of the Avatamsaka (Flower Ornament) Sutra, more than 1600 pages, one of the most stimulating of Mahayana texts. It is replete with luminous visions of bodhisattva activity and exalted experiences of mind and reality, conveyed with lush, psychedelic, evocative imagery. As the inspiration for the Chinese Huayan teachings (Kegon in Japanese) it is highly influential for all East Asian Buddhism. In his Huayan class I attended, Cleary mentioned that he recited aloud the entire Avatamsaka Sutra in Chinese seven times before he started translating it. Cleary’s Entry into the Inconceivable is one of the most valuable books on the dialectical Huayan philosophy, providing translations of the dense, profound writings from the Chinese Huayan founders. As with most of his translations, Cleary’s introductory commentaries are extremely informative.

Among his numerous Zen translations are the three koan collections most utilized in current practice, The Book of Serenity (most important for Soto Zen) and The Blue Cliff Record (translated with his brother J.C. Cleary). Thomas Cleary also translated the Gateless Barrier, titled Unlocking the Zen Koan. His translations of Dogen include Shobogenzo: Zen Essays by Dogen, one of the several books I recommend for those who want to begin study of Dogen. An example of his creativity is Cleary’s rendition of Dogen’s essay “Zenki”, often translated as “Total Dynamic Activity.” Cleary incisively titles this essay “The Whole Works,” which provides stimulating English resonances.

One of Cleary’s initial Zen translations was Timeless Spring: A Soto Zen Anthology, still a valuable source of stories about Soto Zen ancestors in China and Japan. The book includes fine early translations of the “Merging of Difference and Unity” and the “Song of the Jewel Mirror Samadhi” (versions chanted for years at the S.F. Zen Center, now only slightly revised). Timeless Spring provides excerpts from the Chinese 12th century master Hongzhi, which led to my translating the Hongzhi material in Cultivating the Empty Field almost ten years later.

Among Cleary’s many books on Zen, The Five Houses of Zen is also extremely useful, providing fine excerpts from nineteen major figures representing all the five main Chinese Chan branches. A notable small volume from Cleary is Minding Mind: A Course in Basic Meditation, which includes seven meditation instructions from teachers in China, Korea, and Japan. Cleary translated a great many other Buddhist works. His book Buddhist Yoga is a translation from Sanskrit of the Samdhinirmocana Sutra, an important text in the Yogacara or Mind Only branch of Mahayana, highly influential in Zen.

Aside from Cleary’s massive contributions to Zen and Buddhist studies, he translated from the Chinese a great body of important Taoist works, also very useful for Zen practitioners. Cleary’s The Essential Tao contains the root Taoists texts the Tao Te Ching and the inner chapters of the Chuang Tzu. Cleary also translated several books from the later Complete Reality school of Taoism, which interacted with Chan (Chinese Zen) teachings and presented systematic Taoist alchemical meditation practices. These books include Understanding Reality: A Taoist Alchemical Classic, The Inner Teachings of Taoism, The Book of Balance and Harmony, and Awakening to the Tao. He translated the classic text, the I Ching, or Book of Changes, an ancient precursor to Taoism. Valuable not simply as a divination tool as commonly described, but a comprehensive spiritual guidebook, Cleary translated several later commentaries on the I Ching, including from Buddhist and Taoist perspectives.

Other Chinese classics Cleary translated include Sun-tzu’s The Art of War, and related texts. This was certainly his most popular volume. It provides strategies and skillful techniques still applicable to modern business and organizational management as well as military applications. It has been translated into many languages as have many of Cleary’s other works.

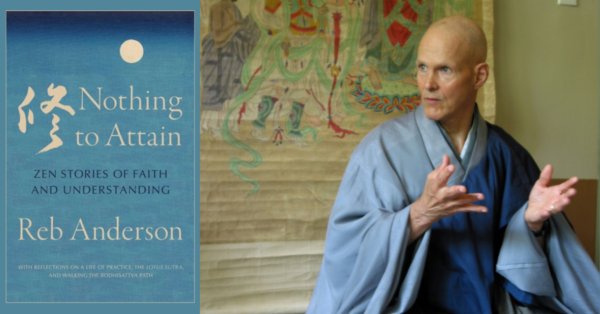

My classes with Dr. Cleary in 1986 occurred shortly after my priest ordination from Tenshin Reb Anderson at San Francisco Zen Center and after five practice periods at Tassajara monastery. I had studied most of Cleary’s translations to that point, including reading the entire Flower Ornament Sutra during study periods at Tassajara. Perhaps that encouraged Cleary to engage in our personal conversations. From these conversations I understand something about the inner reasons for his notable later reclusiveness.

Cleary’s work has been disregarded by some current academic Buddhist scholars because he often did not provide modern conventional academic apparatus, such as notes about textual sources. Indeed, in some of his Zen compilation books I agree about missing source references. Thomas had a Ph.D. from Harvard, so he certainly knew those modern conventions. But he told me that he disliked modern academic standards and disputation; he preferred to follow traditional scholarly principles from the cultures he was translating. He was not translating or writing for an academic audience, but for a much wider readership including spiritual students and practitioners. Cleary generally disliked large, formal institutions, with their potential for ossified, self-serving perspectives.

Thomas Cleary told me that he had suffered from asbestos exposure during a job he had as a teenager. This may well have led to the diseases he eventually died from. I did clearly observe that it was physically and perhaps neurologically painful for him when he had to respond to students’ questions that he considered ignorant or disrespectful of course material. At such times he seemed brittle and in genuine distress. After that year, Dr. Cleary withdrew from teaching at CIIS or any other academic forum. I did not have any further personal contact with him, although I attended a brief series of lectures that he presented in the East Bay a year or two later. I believe that Thomas Cleary decided that his time was best spent producing the enormous volume of valuable translations he has left us, rather than teaching small groups of students.

Thomas Cleary’s many brilliant translations from various spiritual traditions is a tremendous gift. May all peoples benefit from his extraordinary legacy. I used to say that Thomas Cleary was the American Kumarajiva, who was responsible for translating a great number of Buddhist texts into Chinese (with the assistance of disciples and a government bureau of translators). However, I would now instead declare that Kumarajiva was the Chinese Thomas Cleary.