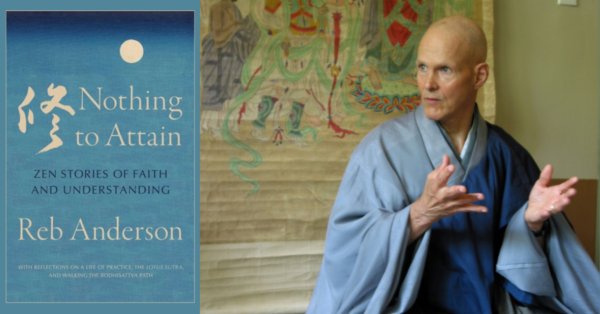

On Friday, October 26, Jack Weller will be speaking at San Francisco Zen Center about his memories of Suzuki Roshi and the early days of SFZC. His talk is part of a series of Fourth Friday talks presented for SFZC members only. This article may be of interest to non-members as well as members.

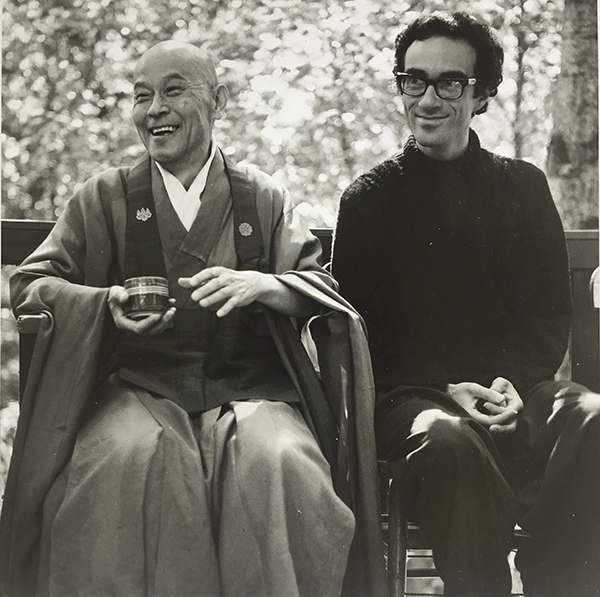

Suzuki Roshi and Jack Weller at Tassajara, June 7, 1970

Jack came to Zen Center in 1967. A friend in New York had told him about an article in the Village Voice about Tassajara, which was to become the first Buddhist Monastery in the United States, and Jack knew that he needed a meditation practice. By that time, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, who had come to the City to live and work with the Buddhist community at Sokoji Temple in Japantown, had included in his focus the Western students who had gradually come to sit with him.

Jack had grown up in Vancouver, British Columbia. His father was a business man, who had a large chain of candy stores in England before emigrating to Canada. Jack’s family celebrated the Jewish holidays but when his mother took a class in World Religions she told him that if she had her life to live over again, she would be a Buddhist. “And don’t talk to your father about this,” she said, “But I want you to listen to this radio program.” It was Alan Watts. Jack was eleven or twelve years old.

“My mother was more than my mother,” Jack says.”She was my teacher.” After his mother died, Jack’s interest in Zen Buddhism continued.

As with many of us, some life changing events had woken Jack up to the truth of impermanence. He had had rheumatic fever as a child. When he was 27, he was told that he needed to have open heart surgery and afterwards his doctors said he had a 50% chance of dying. Two of his fellow students had committed suicide, partly due to the stress of the PhD program in Philosophy at UCSB. Jack was a graduate student there and had finished all the courses he needed, and he had been working as a teaching assistant in Philosophy but after his heart surgery, he knew that he couldn’t return to the stress of the university. He called Zen Center and was told that he wouldn’t be able to go straight to the monastery at Tassajara—it was recommended that students practice for six months in the City first.

“I’ve been remembering about when I first came to practice,” Jack told me. “Since I was a child, I could sit full lotus without pain. So when I started sitting, I started with full lotus. On Bush Street, we would sit zazen and the zendo was the same room as the Buddha Hall. We would sit and then we would stand and chant. When it ended, Suzuki Roshi would go to the door and he would look into your eyes and bow to you as you left the zendo. It was very personal … Suzuki Roshi would hit everyone on the shoulder with the kiasaku during the first period of a sesshin, not hard, but as if to say, “Wake up everyone!”

Jack met Yvonne Rand, who was then secretary of Zen Center, and she helped him get acclimated. There was an apartment across the street from Sokoji that was open so Jack moved in with a student named Reb Anderson. They would go to zazen every morning.

Jack spent nine months practicing with Suzuki Roshi on Bush Street but Katagiri Roshi encouraged Jack to return to school to take his final exam. He passed the exam and received an MA in Philosophy. He went on to practice at Tassajara for a year and then came back to the City because he needed to earn some money. He agreed to teach some classes at San Francisco State, including a class on mysticism, for a professor who was on leave.

Jack was the first Zen Student to move into the building at 300 Page Street while the building was still in escrow. Jack lit incense from Eiheiji Temple the first night he was there. He was told to choose a room so he picked one on the third floor. About a week later, David Chadwick moved in and, after that first week or two, the sale finalized and Suzuki Roshi came over to visit. Jack showed him around the building and Roshi was very excited and happy. They went up to the third floor and they looked across the way at the building on the corner and Suzuki Roshi said, “We should buy that building, too”

“Suzuki Roshi’s stature wasn’t always apparent,” Jack told me. “He appeared very ordinary. Extraordinarily ordinary! But I was always moved by the power of this teacher; his presence, his smile, his kind intensity, and the connection I felt with him.”

Jack attended the ceremony at Zen Center where an ailing Suzuki Roshi installed Richard Baker as Abbott in 1971.”Suzuki Roshi was very ill but somehow he summoned the strength to come to the ceremony. Suzuki Roshi’s son Hoitsu Suzuki, the Abbott of Rinso-in, was on one side of him and his wife, Mitsu Suzuki-sensei, was on the other and they were holding him up. He couldn’t speak but he had a staff that Alan Watts had given him that Alan had brought from Japan. It had rings on the top that jangled as the staff hit the floor. He pounded that staff on the floor as he entered and as he left the Buddha Hall.”

The hitting of the staff at the Mountain Seat Ceremony felt to Jack to be Suzuki Roshi’s last Dharma communication to us. Roshi died on December 4, 1971, during Rohatsu Sesshin.

Jack had just moved into 340 Page Street and was the first Zen student to live there. Gradually the other tenants moved out as Zen students and families moved in. Jack and Mary Watson have been married for 38 years. Mary is an educator and a practicing member of Zen Center. Their now adult son, Daniel, grew up at 340 Page Street.

Though tempted to be ordained as a priest, Jack felt strongly that his path was to be a teacher. During his academic life, he had the opportunity to study with Edward Conze and Huston Smith, as well as with Paul Weinpahl, who had gone to Japan to practice at a Rinzai monastery and was one of the first Westerners to recognize zazen as essential to Zen practice. Jack has taught philosophy and Buddhist Studies at San Francisco State, the California Institute of Integral Studies, Mills College, The University of California Extension, Santa Barbara, UCLA, and John F. Kennedy University. At the California Institute of Integral Studies, Jack created a new kind of master’s degree in Expressive Arts Therapy; dance, music, art, sculpture, poetry, all of the arts combined.

Of practice and of life, Jack says, “There is brightness in darkness. The darkness is non-verbal. You can be in that darkness and be alive. The important things in life, you can’t know in words.” He went on, “After Suzuki Roshi died, I realized what was missing for me was the compassion and loving part of Buddhism, not a verbal teaching but what I felt when I was with Roshi. I have looked for teachers that have that and I met two women teachers in the years soon after Suzuki Roshi died. Tseda Lehmo is from Tibet. Rina Sirkar, from Burma, I’ve known for years and years. She led a meditation group and she would begin and end with the Metta Sutta. Without putting it into words, Suzuki Roshi had that loving kindness in his being. More recently, I have been a student of Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese monk and peace activist.”

For the past 20 years, Jack has been working on his memoirs about Suzuki Roshi. He shared a story with me:

“Ed Brown and Meg Gawler were married at Tassajara and the reception was under the trellis that ran along the path in front of the old zendo. There was a table with glasses of champagne and Suzuki Roshi helped himself to a glass. When he was about to take a second one, Mrs. Suzuki came up to him and said something like, “One is enough!” Suzuki Roshi nodded and turned away. He saw me standing nearby with a full glass of champagne and came over to me. Looking at me with laughter in his eyes, he took the glass from me and drank it.”

As you are walking from the main floor of 300 Page Street to go down the stairs to the Zendo, there is a screen with Suzuki Roshi’s shadow printed on it. This slight man, in his all too short time with us, lives on in the hearts and lives of his students and in the life of Zen Center and practitioners of Zen all over the world.

—Laura Burges, October 2018