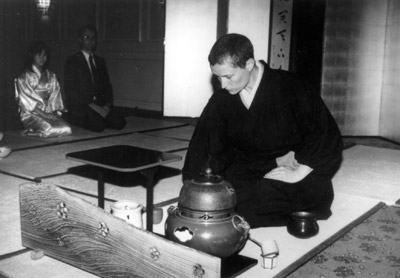

A young Fu Schroeder performs tea ceremony

A young monk performs

Tea ceremony—

Hanging kettle sways slightly

I was so pleased to be asked to speak today on this wonderful occasion of Suzuki’s Sensei’s 100th year of life, and to join all of you in celebrating the publication of her 100 haiku collection called A White Tea Bowl. A deep bow of congratulations to Sensei (Okusan), and a deep bow to Kate McCandless and Kaz Tanahashi-san for this beautiful tribute to her life and her art.

When I first heard the title of her collection of poems, I thought to myself, I’ve never seen a white tea bowl. and then I thought how very much I’d like to see one.

Tea ceremony has that effect on those of us who practice tea together. We love to see, touch, and talk about the objects that have been brought into the tea room for that day. And to hear what are called the transmission stories: stories about how and when this object was made, what kind of clay or glaze was used, who the artist was, who acquired the object, and who is taking care of it now.

It’s these stories that empower these objects, which reveals to us their aura and establishes the strength of their presence. For example, there’s the tea bowl itself, the chawan, such as the one given to my teacher by her mother over 70 years ago when she was just a little girl, or the one memorialized by Suzuki Sensei in the haiku written for her husband after he had died:

I pour sencha into the

White porcelain tea bowl

He loved

And then the tea scoop (chashaku), some of them carved by Suzuki Roshi’s son, Hoitsu Suzuki. The tea whisk (chasen) and the lovely tea caddy (natsume), inside of which is a little mountain formed by my teacher from the powdered green tea.

And eventually we talk about the items in the alcove of the tea room called the tokonoma, such as a lovely woven flower basket that Suzuki Roshi had repaired for their good friends here in America, Mr. and Mrs. Nakagawa—very good friends indeed, who were kind enough to accept into their home Suzuki Sensei’s students when she returned to Japan in 1994.

Hanging above the basket, the scroll often written by a famous Zen teacher in celebration of the season, the incense container. . . and then so much more.

Week after week, year after year, as a guest, you enter the tearoom sliding on our knees, and then bowing to one another again and again as we watch the rebuilding of the charcoal fire, offering of handmade sweets, mixing the thick green tea, then more sweets, then thin green tea. Until you can’t take another bite of anything. You are completely full and utterly content. . . another of those rare and transitory delights. And then, finally, we slide out the door and back out into the world behind the screens.

Tea is all about feelings, as far as I can tell. Those exquisite feelings that come from being with old friends, from learning new things, from honoring age-old craft, but, most of all, from the dance. It’s the dance I think that gets you hooked on tea. Starting with your own tiny toes wrapped inside those tight white tabi.

And now it’s your turn to be the one making tea. Once your guests are seated and ready, you open the door, bow, stand, and enter the room to take your place by the fire and the hot iron kettle: chanoyu means “hot water for tea”.

You take a few breaths and then you completely let go. Because there is utterly no way to remember what you are supposed to do next. You have to rely on your body—the body which has been carefully taught over many years of repetition this pattern of intricate and exquisitely linked movements of your eyes and hands. If you miss one step you will quickly discover that there’s no place left to go as you become frozen in your tracks.

Tea is in fact a very tightly woven net of highly visible consequences from which there are only a very few elegant ways to escape. Mostly your fellow students giggle when you drop the whisk or forget when to add the water.

My favorite story about making big mistakes is the one that occurred in front of a large audience. The woman who was performing the tea ceremony over there in Japan was quite old and venerable. There is the particularly challenging seasonal form that involves unhooking the kettle of water which is hanging from a iron chain above the fire on its thick layer of ash, and moving it up a few links, and then, having done a few things with the fire, moving the kettle back down again.

There’s a saying in tea that you should lift heavy things as if they are light and light things as if they are heavy. So this old woman lifted the heavy kettle skillfully—however, she couldn’t really see so well and missed the hooking onto the link up above.

The kettle fell into the fire and a great cloud of ashes rose up in all directions. Without changing the expression on her face she reached down, lifted the kettle, hooked it correctly, and continued making tea. That’s what I call supreme emotional intelligence.

So once those of us of somewhat lesser intelligence have become frozen during tea, kindly—or not—your teacher will remind your body of what it needs to do next. I can still hear Suzuki Sensei’s voice ringing in my ears, “Fu-san, many times I’ve told you…little front, side-o, side-o,” referring to the placement of your fingers on the tea bowl, one of the most basic and simplest of instructions.

“Fu-san . . .”

“Hai! Sumimasen [forgive me].”

If all goes well, which it rarely does, it will take about 40 minutes to navigate the minute instructions required to produce three tiny sips of bright green tea. All the while your knees are on the mats, at levels of discomfort that it’s hard to imagine one would ever voluntarily be willing to bear . . . and yet, for unknown reasons, you stay there until you’re done. It’s especially at times like that when the famous saying written on the scroll comes to life: “Tea and zen are one.” Staying until you are done.

It’s all about feelings. Feelings that lead you to know how wonderful it is to be alive. To be standing, walking, eating and visiting with a friend. Feelings that are all too easy to forget. And so we practice them again and again . . . practice having feelings. All kinds of feelings.

These instructions on how a make a bowl of tea have been kept alive through centuries, for the most part in Kyoto, by a huge consortium of tea practitioners, tea growers, craftsmen and patrons.

Personally I have decided, after nearly 30 years of studying tea, that the entire enterprise is designed to challenge and thereby to re-educate our neuronal pathways: the pathways of form, feelings, perception, impulses, and consciousness. The very five heaps that make up, in the Buddha’s teaching, what we call the self . . . the illusory self. And although not truly there, it’s the only thing we’ve got that can be educated.

When I first decided to ask Suzuki Sensei if I could study tea with her, my motives were less than pure. I had no idea what tea was nor was I particularly interested in finding out. I wanted to get close to Suzuki Roshi, who had already died, and whose memory and reputation at Zen Center was the living basis for the community. Everyone was grieving who had known him. And there was his wife who had known him best of all. I wanted to hear her speak about her husband.

Which she rarely did. She didn’t have to. Suzuki Roshi, as with the Buddhas before him, wasn’t gone—he was embodied in those who had loved him. He still is. And so is she. That’s how it works. You love your teachers for all the things they have given to you through their selfless practice. Lifting heavy things as if they are light and light things as if they are heavy. I love Suzuki Sensei because she was my teacher. And the parts of myself I love best have come to me from people like her.

All of us can think back on those people who opened us up to the light of the world. Of course our parents gave us the initial boost with language, walking, and hopefully cleaning our rooms. Then we went off to school.

My first real teacher from the big world outside of home was Mr. Brown in the third grade. He took our class out beyond the asphalt playground into the fields of weeds behind the chain linked fence. And then he turned over a big rock. Wow! There were so many tiny little creepy things moving quickly away from the light. It was so disorienting to experience the world as more than what it seemed . . . more than human, out of control, and deeply mysterious. Thank you, Mr. Brown; thank you, Suzuki Sensei; thank you, Reb; thank you, everybody, for disorienting me again and again.

There are a few well-known stories about the practice of tea, some from within the tea tradition itself and others from Zen. The roots of tea and Zen have been entwined from their earliest beginnings in China. In fact, it’s rumored that the tea plant itself grew from the eyelids of Bodhidharma when he tore them off and cast them to the ground in his determination to stay awake while sitting upright in his cavern. That’s why those Daruma dolls have those big unblinking eyes. Something to scare the little kids.

It may be, more factually, that the drinking of powdered green tea, called matcha, entered Japan from the Song Dynasty in China at the end of the 12th century with the Buddhist monks who had gone there to study Zen. At first it was used to overcome drowsiness during long periods of meditation and also as a cure-all medicine, being fully loaded with both caffeine and vitamin C. Eventually tea took hold within Japanese culture as not only an medicinal drink but as a tasty beverage, and as a consequence the numbers of tea plantations, and the comparisons among them, increased to become one of the major industries in Japan.

Within a few hundred years the making of tea, the value of the tea utensils, and the writing of poetry all converged as warrior, merchant and upper-class sport.

Around the 15th century the practice of making the tea in front of the guests, rather than having it brought in from another room, became the cultural norm. This act of making a bowl of tea in front of others is called the temae. It’s the temae that we study in our classes each week.

Of the many stories about the tradition of tea, I particularly like the ones about Sen no Rikyu, the 16th-century tea master who perfected the tea ceremony and raised it to the level of an art. Sen no Rikyu reestablished the practice of tea, in all of its aspects, in keeping with its earlier monastic forms. Under Rikyu, the temae, the utensils, the tea-garden landscaping and tea-house architecture were all governed by such aesthetic ideals as wabi (meaning deliberate simplicity in daily living) and sabi (appreciation of the old and faded) —thereby the saying that “Tea and Zen are one.”

So one day, Rikyu was invited by a tea grower, a farmer, to come for tea. The tea grower was very fond of the tea ceremony and practiced as often as time allowed. Rikyu arrived at the old man’s tea house, bringing with him one of his promising young disciples as second guest. Being very nervous, his hands visibly shaking, the grower made a number of obvious mistakes. And yet at the finish Rikyu said to him in all sincerity, “This tea you have made is the finest.”

On the way home, the disciple asked Rikyu how he could have made such a comment given the amateur performance by that man. Rikyu replied, “He made tea for me with his whole heart.”

When I think about Suzuki Sensei, wholeheartedness is certain the dominant quality through which she lived her life. Whether she was teaching us tea, doing her daily exercises up and down the hall, singing children’s songs at top of her lungs, or carefully bowing each time she past in front of the Kaisando upstairs and each time she past by one of us, she was wholehearted.

Mitsu Suzuki Sensei, left, and Meiya Wender, right, with, behind, Fu Schroeder and Harumi, Mitsu’s daughter

And she still is. When Meiya and I went to Japan last fall we were so blessed to be taken to see her in her home in Yaizu where she now lives with her daughter, and nearby, her great grandchild. She spend nearly two hours with us showing us the photo albums Zen Center had given her years ago full of pictures of all of us. She pointed to the tea kettle sitting in the corner, smiled at me and said, ”There’s your old friend, Fu-san.”

I think she knew very well that Zen Center needed her to stay here for a while until the shinmei, the new growth, had a chance to strengthen and to flower. Her presence and example were a through-line from temple life she had known in Japan to our sincere efforts to ground our own culture’s practice in Suzuki Roshi’s simple and profound teachings.

She took so many of us under her wing personally—and yet it wasn’t really personal. She wasn’t my friend or parent. She was my teacher. She had dharma to offer, as had her husband, his son and now their grandson who have each taken the long plane ride to come here to America and to teach.

I think we are learning. I feel we are and I trust that we are. And yet, it seems best if we’re never quite sure. There is so much for each of us to learn—among them, how to be good hosts and good guests, a profound social form which among all the world’s cultures, the tea ceremony may know best. It’s also what Zen practice may know best: that host and guest are not two and yet they are not the same either. There is something in that relationship that each needs to learn from the other—by taking turns. By altering our points of view.

Here’s another very good story, this one from the Zen tradition about a tea gathering of two Zen monks and a local samurai lord by the name of Sendai.

The monk, named Tetsugyu, had invited Lord Sendai to tea when his dharma brother Cho-on dropped by for a visit. Lord Sendai invited Cho-on to join them for tea. Tetsugyu had chosen an especially precious antique tea bowl that Lord Sendai had given him, which he set down on the tatami mat as he began to make tea. After drinking the tea, Lord Sendai followed the tradition of admiring the bowl, after which he passed it to Cho-on so he might do the same.

Cho-on suddenly reached out with his ceremonial stick and smashed the tea bowl. “Now look at the authentic tea bowl that exists before birth,” Cho-on said.

Tetsugyu turned pale and nearly fainted, but Lord Sendai remained upright and present, saying to Tetsugyu, “I gave you that tea bowl but I would like you to give it back to me now. Before you give it back, please have it glued together and have a box made for it. On the box I ask that you write the name of the bowl, which I now give as ‘The Authentic Tea Bowl Before Birth.’ I will reverently pass it on to my descendants.”

This story is about tradition, and whether or not we are holding on to a tradition without understanding its essential meaning. For the Zen student, the essential meaning of things is that they don’t exist. That their fundamental characteristic is a lack of inherent existence. So do we break the tea bowl, like “whatever”, or, like Gollum in The Lord of the Rings, do we try to possess it? “My precious.”

The essential meaning is that there is no essential meaning referring to something other than itself. While making tea, make tea. While eating lunch, eat lunch. While washing the dog, wash the dog. So simple and yet almost no one can pull it off—pull off the veil of concepts through which we continuously evaluate and view the world: “That’s my lovely tea bowl!” “Today I’ll be having soup for lunch.” “What dog?”

Practice is not a matter of time or some duration of time. It is always exactly what is happening right now. It is always in the form of you yourself as both host and guest of the present moment. Whether you are walking, kneeling, serving, or receiving the offering. The practices of awareness arise as boundless stream when you and world appear inseparably together. Nothing to hold on to, nothing to break, no one to protect or to hate.

How about you? Would you like a bowl of tea?

The last time I made tea for Suzuki Sensei before she returned to Japan I was having a pretty hard time. Mostly because I kept crying. When I finally finished whisking and looked into the tea bowl, there were tiny lumps floating on the surface. I bowed and told Sensei I was so sorry about the lumps. When I looked up, she was smiling at me and then she said, “Fu-san, enjoy the lumps”.

First calligraphy of the year—

Today again

I write “Beginner’s Mind”

From a talk given at City Center, on April 26, 2014

0 Comments