David Bowie’s intuitive grasp of the truth of constant change launched him from an almost-monk into a shape-shifting master of musical ceremony, writes Zen priest and writer Roberta Werdinger as she investigates the way of the Bowie-sattva

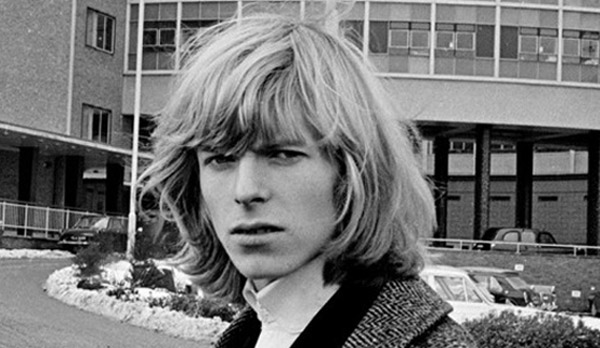

The teenage David Jones, as he was then, in 1964, just before a Buddhist teacher dissuaded him from becoming a monk

It is a familiar story. A young seeker shows up at a place of worship and instantly connects with a teacher he will take as his guru. So taken is he with the dharma that he prepares to shave his head and become a Buddhist monk. But here the narrative takes an unconventional and world-changing turn. A teacher from that very Buddhist path dissuades him: He would do better, he is told, to stay in the world and become an entertainer, where he can ultimately do more good than as a monk.

The year was 1965, the place was London, and the young seeker was the teenage David Jones. Within two years he would take the stage name of David Bowie and release his first album. The guru he connected to was Lama Chime Rinpoche, who recently released a video tribute to him. “Silly Boy Blue,” from that first album, documents the experience.

It must be admitted that David Bowie’s rock-star life included liberal doses of sex, drugs, and other markers of high living, and that he didn’t sustain a Buddhist practice. (As he grew older, he gave up his cocaine habit and settled into a long and, from all accounts, happy marriage with the Somalian model and entrepreneur Iman Abdulmajid.) Nevertheless, in an interview he stated, “I have always followed some of the tenets of Buddhism, especially the one about change.”

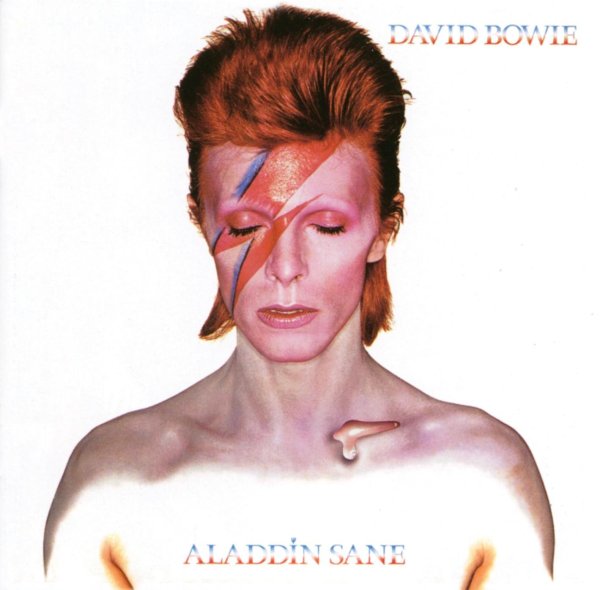

Aladdin Sane, also released in 1973: The hit “Jean Genie” is “perhaps the most danceable song in the known universe”

Indeed. Riding successive waves of the stupendous cultural transformations of the last several decades—sometimes at the crest, other times ensconced comfortably in the middle or rear–Bowie was a gaudily lit showboat of change, inventing and discarding musical genres and personae with a restless intelligence that has helped make our era the vivid, globalized pastiche that it is. In his demonstration of how identity is fashioned and his willingness to exchange one mode of being for another, he gave a permission that liberated us all.

David Bowie’s concerts were full-on theater, employing lighting, elaborately outfitted musicians and dancers, video, and towering stage sets for their effect.

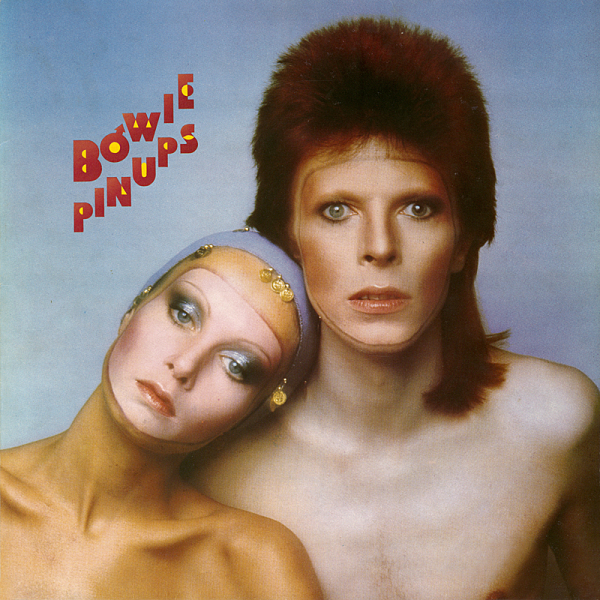

Migrating easily between the mainstream and the avant-garde, Bowie studied and incorporated a dizzying array of styles and cultures: German Expressionism, Japanese kabuki, African-American soul, jazz and disco, French cabaret, British punk. He was able to invent new musical forms by boldly and unapologetically assimilating that of others. Each album seems to have a musical scion presiding over it, from the whimsy of mid-sixties Kinks in his eponymous first album to The Who’s angst-driven drumbeats in PinUps to the Stones-inspired, Dionysian abandon of Aladdin Sane, whose hit “Jean Genie” is perhaps the most danceable song in the known universe.

Bowie with Twiggy on the cover of PinUps, his 1973 collection of cover versions of tracks like “I Can’t Explain” and “Shapes of Things”

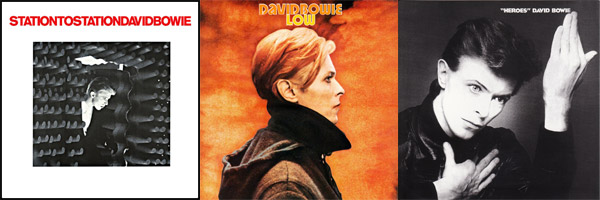

In 1975, in the middle of a decade he did much to define, Bowie had already abandoned his glam persona and swerved into soul, where he appeared as the Thin White Duke, a moody dreamer on the album Young Americans. In the next two years, he released three albums, Station to Station, Low, and Heroes, the last two of which were recorded in Berlin with the help of fellow glam rocker and electronics wizard Brian Eno and under the influence of Lou Reed. All three albums are masterpieces, melding Bowie’s ability to throw off hooks and hits (including “Golden Years” and “Heroes”) to the murky, moody synthesized soundscapes of art rock.

I’d spent the late Seventies and Eighties as a wannabe artist firmly in the hold of a punk sensibility. With his neon-colored, spiked hair, Bowie was one of the progenitors of punk fashion. His 1969 hit “Space Oddity,” with its psychedelic evocation of spinning through the stars, and the outrageous postures of the glam era were firmly welcomed by myself and fellow travelers, but when Bowie made a disco album in 1983 and then verged into industrial and metal sounds, I lost interest in him.

Golden Years: Wannabe artist Roberta Werdinger in 1984 with then partner Philip Gammon

In the rather stuffy manner that can afflict members of a youthful movement, I judged Bowie superficial, selling out his underground affiliations for a chance to be popular. But I was wrong. I understand now that David Bowie wasn’t superficial; he was so artistically deep that he had to move between several styles in order to express himself completely.

While my artistic ambitions floundered over a lack of discipline, I could have taken a page from David Bowie, whose Dionysian excess was counterbalanced by a firm understanding of form. Bowie was always writing sonnets, in a way—inserting himself into different stylistic challenges whose strictures had to be negotiated before the emotional truth that would make them relatable could be realized. When he did, the result would be a near-perfect song, at once effortless and mannered, crystalline and catchy. Such a one is “Golden Years,” whose polished, doo-wopping soul verses were riven by the heartbreaking declaration of the chorus: “I’ll stick with you, baby, for a thousand years/Nothing’s gonna touch you in these golden years.” …Heartbreaking because its promise is emotionally true, yet impossible to carry out.

When I began studying Buddhism, the teaching of anatman (no-self) frightened me, as I imagined my body and mind rubbed out in some kind of cosmic convulsion. But in fact, the realization of no-self only means that the possibilities of the moment can be expressed with more clarity and distinction. Bowie seized the moment that presented itself amidst the cultural and political upheavals of his time to craft personae that advanced that era into a future no one could then imagine. Discussions of gender fluidity were not on the near horizon when Bowie shaped his hair into a spiky mane, dyed it bright orange, and donned psychedelically-patterned, skintight jumpsuits as Ziggy Stardust in 1972. In an era when LGBT people were at pains to deny their queerness so that they could avoid the hatred society aimed at them, Bowie walked the other way. He was a straight man who posed as gay, making sure he got photographed kissing Lou Reed. (It’s a little hard to pin down Bowie’s sexuality—he declared his bisexuality in one interview, retracted it in another, and has mainly formed romantic alliances with women.) In doing so, in blurring the boundaries of male and female presentation, he made liberation possible for many.

Bowie’s three soul masterpieces of the mid-Seventies, Station to Station, Low, and Heroes

The notion of gender as a series of culturally coded gestures—as a performance—wasn’t widely dispersed in the modern Western world until 1990, when Judith Butler wrote the book about it (Gender Trouble). Meanwhile, Bowie had already been busy enacting it. Gay men especially felt gateways open as Bowie became an icon of the glam movement. Rockers such as members of Mott the Hoople and Queen donned androgynous clothing and painted their faces. The musical quality of these groups varied; in any case, having helped start a revolution that celebrated sex even while it redefined sexuality, Bowie was on to something else.

In blurring the boundaries of male and female presentation, Bowie made liberation possible for many

In an essay exploring the relationship between art and Zen meditation titled “Do You Want to Make Something Out of It?” Norman Fischer writes: “The reason we need art so desperately I would say is that the world and we ourselves persist in being made.” In the midst of a world of ever-increasing information and stimuli, “The work of art, by contrast, is entirely organized and therefore peaceful.” Art is an artifice–both words trace back to the word for making. Make-believe, making up, and make-up—all were Bowie’s territory. Every moment, any sensation I can call real is the result of endless conditions that are external to it. Dependent co-arising means that everything is endlessly and fabulously made. To insist that my feelings and reactions are “natural” may be a way of hiding their madeness, of highlighting my subjective experience and making out of it a whole world, blinding me to its consequences.

Thus we need showmen like Bowie, who was not a clown so much as an elegant entertainer, ever enwrapped in artifice. If there was a pose to take, Bowie took it. But it wasn’t because there wasn’t a sincere person underneath the mask who wanted to escape reality. It’s because Bowie needed the masks in order to make sense of that reality as it unfolded in the often bewildering tumult which the Sixties and Seventies unleashed. His intuitive grasping of the truth of constant change launched him from an almost-monk into a shape-shifting master of musical ceremony.

After waiting so long for his spaceship to come, David Bowie’s been launched into the cosmos. He’s been changed, beyond what we can understand. But then, he was always about changing us.

Roberta Werdinger lived and studied at Tassajara and Green Gulch Farm Zen Centers from 1995 to 2006 and was ordained by Tenshin Reb Anderson in 2000. She currently lives, writes, and strides the woods in Mendocino County, where she hosts “Maps & Legends,” a show exploring rock & roll history, on public radio station KZYX. She is especially interested in the intersection of Buddhism, ecology, and the arts.

Roberta Werdinger lived and studied at Tassajara and Green Gulch Farm Zen Centers from 1995 to 2006 and was ordained by Tenshin Reb Anderson in 2000. She currently lives, writes, and strides the woods in Mendocino County, where she hosts “Maps & Legends,” a show exploring rock & roll history, on public radio station KZYX. She is especially interested in the intersection of Buddhism, ecology, and the arts.