by Kyva Holman

After an incident occurred close to home, Green Gulch resident Kyva Holman reflects carefully on how to juggle myriad considerations where race and Buddhist practice intersect with the complex conditions of our modern world. Kyva shares his personal perspective through the invitation of SFZC’s Cultural Awareness and Inclusivity Committee.

For some, taking refuge in Buddha, Dharma and Sangha is not abstraction. It’s front-and-center reality. But what if that refuge is breached?

Buddha figure from Vietnam

Recently, a milder example of the racialized profiling all too often leading to events like those in Ferguson, MO, occurred just beyond the property of my sangha, Green Gulch Farm Zen Center. An African American male student was smoking a cigarette and minding his business at the beach when an officer approached him under the suspicion that he’d been rifling through the garbage. This student had gotten the cigarette from a tall, stringy-haired, shirtless white man who looked, according to the student’s account, like someone who might be inclined to go through a trash can or two. But this person was never questioned. The student, also tall, with long dreadlocks, admittedly riding a grubby bike, was assumed by the officer to have been the culprit and was told to move on.

When this student recounted the incident to a member of the senior staff at Green Gulch he was advised that in such a situation he should immediately notify the center by phone. Perfectly understandable advice, except that it fails to grasp the actual nature of many police encounters with African Americans. When they happen, there is in fact a very small window of time in which extremely clearheaded and cautious decisions must be made to prevent tragic and unnecessary escalation. And since one’s survival is apparently not assured in one of these encounters even with both hands in the air, it’s a bit idealistic to presume that whipping out a cell phone and dialing will have the desired result.

Let me emphasize that one of the myriad things I deeply appreciate about this sangha—the closest thing to Pure Land I’ve experienced in this life—is that people here do seem genuinely interested in taking on the work of confronting “isms”: racism, sexism, genderism, classism, ageism, etc. The need to overcome the invisible, pernicious advantages of “white privilege” is a tough but valuable ongoing conversation.

At the same time, the irony of being surrounded by abundant, high-quality food and getting harassed and treated like a homeless person in one of the top 20 richest counties in the US underscores what is, in moments, the high strangeness of being a black disciple of Buddha in 2015. If we truly take up the inherent emptiness of the five aggregates (form, sensation, perception, formation and consciousness), as the Heart Sutra instructs us to, then truly there’s nothing to trip about. At the absolute level all is transient. But in Buddhism we must reckon with absolute and relative truth. So we also chant: beings are numberless / I vow to save them, dharma gates are boundless / I vow to enter them. This implies a commitment to engage virtuously with an interminable entourage of suffering entities, a willingness to explore realities without bias, without end.

Buddha figure from Thailand

Here are some basic relative truths about racial dharma. We’ve elected, for the second time, the first African American president (or “half black,” a term which suddenly fell into vogue after he was voted in); we’ve had our first black attorney general and more black federal court judges, mayors, governors, congressional members, high-ranking political appointees, scientists, inventors, public intellectuals and wealthy celebrities than ever before. Government policies promoting segregation have been replaced by ones officially promoting inclusion. Antidiscrimination is firmly entrenched in the corporate workplace. The Civil Rights Movement provided a template for cultural pride and self-esteem, and at the same time, official record-keeping allows people to designate themselves as belonging to more than one race, effectively creating various possibilities for self-identification. Young people of all colors exist in a social context that perceives and practices race flexibly.

And yet a whole class of black political leaders, responding defensively to a national climate of resurgent racialized tension (epitomized by outright hatred of Barack Obama), is apparently stymied against effective representation of African American interests. Black unemployment rates are consistently twice that of whites. The National Bureau of Economic Research issued a paper in July of last year titled “The Prison Boom and the Lack of Black Progress after Smith and Welch.” The data is clear: increases in incarceration rates over the last few decades and the precipitous drop of employment rates in the wake of the Great Recession have left most black men no better off than they were shortly after the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1965. Suppression of the black vote, particularly in Republican-controlled states, is naked, vicious, and empowered by the Supreme Court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act—which somehow happened on the watch of the first black president. African Americans endure a host of health-care disparities, and were disproportionately targeted for subprime loans. Since home ownership is linked to financial liquidity, a generation of black economic progress was wiped out when the housing market tanked. Privatization, neoliberalism and penal populism have led to the militarization of minority schools and hyper-criminalization of youth, culminating in the school-to-prison pipeline, vigilantism and fatal policing.

For certain generations these and other social maladies were most visibly expressed in hip-hop: an aggregated artistic subculture with its own extreme karma, forms, sensations, perceptions, etc., which arose essentially out of urban American warzones to heights of worldwide prominence and influence. Some who recall the “golden days” of hip-hop are old enough to perceive its impermanence in disenchanting ways. Before mass commercialization of what is called “rap music,” b-boys and -girls expressed their authenticity and dynamism through a variety of forms (upaya): rapping, turntablism, graffiti, breaking and pop-locking. And for a brief period in the late 1980s and early ’90s a renaissance of black cultural pride and political assertiveness appeared to foreshadow hip-hop’s evolution into a highly effective vehicle for positive change. That didn’t happen. Suppose now that a participant in this culture later encountered a moment of rapturous bliss on a 10-day Vipassana retreat. Transformed thoroughly, such a person might recognize tremendous therapeutic potential in Buddhist practices for their peers and feel inclined to spread the word within an art form fueled primarily by suffering. But Buddhism is still too young in the US to have deep roots in the black community the way that, for example, Christianity does. And when the consumption- and death-obsessed zeitgeist of commercial rap music is factored in, popularizing techniques of concentrated breathing and inner focus in this milieu seem like a long shot.

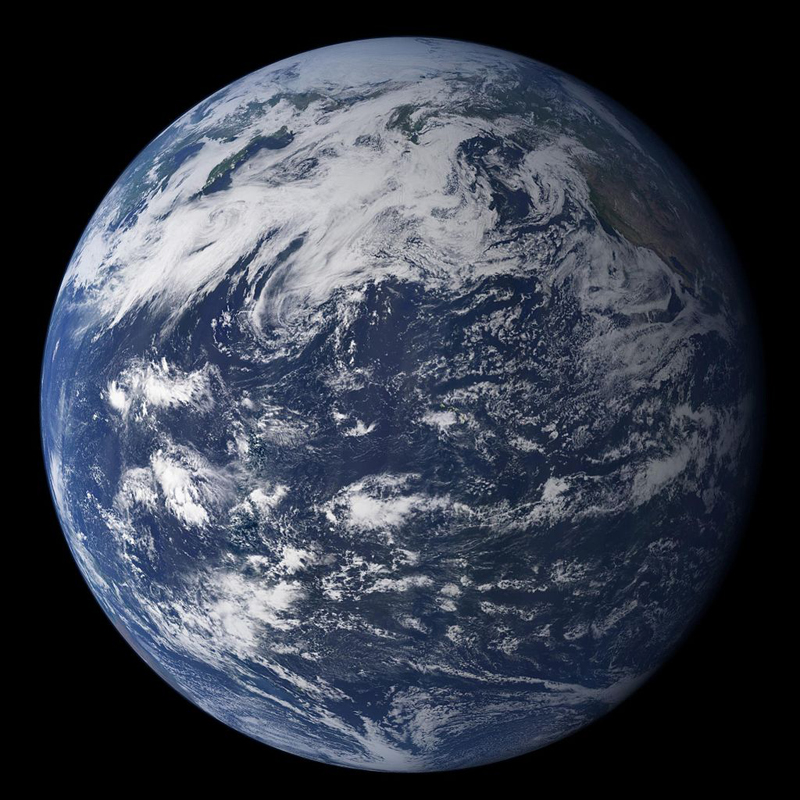

Additionally, the African American disciple of Siddhartha hearing the cries of the world must tune in the encroaching sixth (and first human-driven) mass extinction event, with disappearing forests, melting ice, rising and acidifying oceans, global political and economic illegitimacy, sexual trafficking and animal abuse. There are myriad manifestations of religious extremism, misogyny, domestic abuse and child abuse to somehow reckon with. Beyond these, if said disciple had any affinity whatsoever for their continent of origin, there would undoubtedly be distress over Africa’s long and continuing history of exploitation, the utter distortion and theft of her history, the plundering of her resources, the oppression of her peoples, the resulting civil wars, child soldiers, weaponized rapes, plagues, famines, etc.

Additionally, the African American disciple of Siddhartha hearing the cries of the world must tune in the encroaching sixth (and first human-driven) mass extinction event, with disappearing forests, melting ice, rising and acidifying oceans, global political and economic illegitimacy, sexual trafficking and animal abuse. There are myriad manifestations of religious extremism, misogyny, domestic abuse and child abuse to somehow reckon with. Beyond these, if said disciple had any affinity whatsoever for their continent of origin, there would undoubtedly be distress over Africa’s long and continuing history of exploitation, the utter distortion and theft of her history, the plundering of her resources, the oppression of her peoples, the resulting civil wars, child soldiers, weaponized rapes, plagues, famines, etc.

In Living by Vow: A Practical Introduction to Eight Essential Zen Chants and Texts, Soto priest Shohaku Okumura wrote:

The phrase “wisdom like the sea” refers to an unlimited and boundless perspective. We are like a frog in a well that can see only a patch of sky.… We base our actions on our conditioned understanding, perspectives and opinions. The beginning of wisdom is to see that our view is limited. The view we have at sea is wider than in a well. There is no limitation to something so vast and boundless.

To an extent, what I have been cataloguing here is part of a synergistic, self-reinforcing process which has forced open our awareness as a society from a well-like view to a sea-like one. Our microscopes penetrate subatomic realms of inexplicable quantum strangeness, while telescopes and satellites reveal an inconceivably vast cosmos churning with complexity, energy, and exceedingly violent, exquisitely creative and destructive sequences. Cameras, drones, robots, 3-D printers, Google glasses, virtual reality helmets, total-immersion video games, hard drives and databases with nearly unlimited capacity to store nearly anything knowable, and a staggering array of devices to extract, arrange and manipulate what’s knowable have blown apart our personal and collective vantage points. Our view has been, and mostly remains, limited. Something like perfection of wisdom, prajña-paramita (a very boundary-dissolving exercise), is indeed being approached, but the contest is far from over. Our individual egoic selves, pummeled from every conceivable angle, are lashing out, creating causes, conditions and ramifications we can only minimally account for in the present moment.

And since the present moment is all there is, ephemeral in sublimity or bleakness, anyone might be forgiven for beholding the sum of apparent reality with an exasperated “WTF? What is one supposed to do with all this?” For the Buddhist of African ancestry there are further considerations: how to proceed given that every facet of your existence and human worth has been besmirched within the context of a civilizational paradigm currently in collapse? How can upaya be brought to bear upon the situation given centuries of subjugation and trickery? Is any anger, particularly at injustice, defensible? How much comfort can be taken in the emergent true story of African people—the first people—without lapsing into hubris? How much expression of hard truth erodes compassion and equanimity? At what point does compassion and equanimity prevent expression of hard truth? Do you even realistically have a voice in the conversation in the first place, or a stake? How assertive can you be without creating more suffering—or duplicating stereotypes? How much stillness and silence can you practice before you’re complicit with injustice? And what exactly do you do when the conditions you seek refuge from are as close as the property borderline?

Kyva Holman

Our compassionate founder, Great Teacher Shogaku Shunryu advised in Zen Mind, Beginners Mind that the goal of practice is simply to discover and express our true nature. Before attainment this nature will seem like an awesome power, but afterward it’s nothing special. To study the self is to forget the self. Since everything is metaphorically on fire, including us, we ought to burn ourselves completely in every undertaking, leaving no trace. Concurrently, we shouldn’t try too hard. What these seemingly conflicting notions point to is what Robert Thurman refers to as tolerance of cognitive dissonance. There’s nothing to be done, nothing that can be done, and yet you can’t do nothing. The situation is irreconcilable. Life is terminal, so chop wood, carry water, and get on with it. When you sit, you sit and nothing else. When you’re preparing meals, just prepare the meal. When conversing, converse. A more streetwise way of saying it is play your position. Things will take care of themselves. Sooner or later they always do. We all suffer immensely as the long arc of history bends wearily toward justice. But that’s exactly what it’s doing.