Published by Lehigh University Press, with Rowman & Littlefield, 2014

Review by Catherine Gammon

Once upon a time, not so long ago, a young Zen student practicing at Tassajara read Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick on the suggestion of a friend at the monastery. Maybe Daniel Herman would have gone on from there to study literature and complete his PhD, even to write his dissertation on the very novel and the very subject, without the happy circumstance of having met Melville’s whale for the first time in the mountains of the Ventana Wilderness, in the deep heart-opening canyon that is Tassajara. Maybe that dissertation would even have become a book. And maybe not. Certainly not this book.

Like Melville’s narrator Ishmael, Daniel Herman introduces himself before he guides us carefully into the world of Moby-Dick, introducing at the same time the lens through which he will read the novel: the lens of a Zen student. This is an almost magical and apparently inevitable pairing, as if Moby-Dick had been waiting for just this person to come along and write about it in just this way.

Like Melville’s narrator Ishmael, Daniel Herman introduces himself before he guides us carefully into the world of Moby-Dick, introducing at the same time the lens through which he will read the novel: the lens of a Zen student. This is an almost magical and apparently inevitable pairing, as if Moby-Dick had been waiting for just this person to come along and write about it in just this way.

Herman brings to his reading of Moby-Dick an intimacy inextricable from his practice experience and from his deep sympathy for Melville and his works. Together these origins make Zen and the White Whale unusually moving for a scholarly study, quite independently, I would guess, of one’s previous knowledge of Moby-Dick or the dharma. And Herman’s whole project and execution reaffirm the possibility and understanding of literary reading and writing as a dharma practice.

Although this is a work of literary criticism, well documented with sources and citations, Zen and the White Whale is delightfully free of theoretical jargon, and as a dharma reading, it is free of jargon as well. Herman intends his discussion to be accessible to anyone familiar with Moby-Dick, not dependent on prior practice of Zen or knowledge of buddhadharma, and I would take this intention a little farther to suggest that the reader need not already know Moby-Dick either, so skillfully does Herman guide us through the novel’s difficult waters. And those of us who do know the novel and are Zen practitioners also may find here the pleasure and danger, both, of being inspired to venture into the novel once again, with our Zen eyes and our Zen hearts open.

Zen and the White Whale begins with the observation that “Moby-Dick and the teachings of Zen Buddhism share a central premise: that the ultimate truths of the universe cannot be distilled by conventional understanding, and that our ‘intellectual and spiritual exasperations’ arise from a desperate need for concrete answers to these ungraspable truths.”

From this assertion, all else follows. The book’s architecture is straightforward. First establishing the Buddhist texts Melville would have been familiar with, both those he is known to have read and those he is likely to have read, Herman goes on to read the novel alongside those teachings, using both the terms the 19th-century texts made available and the language of contemporary Zen teaching and teachers to illuminate Melville’s explorations—and he accomplishes this journey with the lightest possible touch.

From the start Herman expresses the intention to offer a reading without attaching to it, and it is the congruity of this intention with the method and spirit of Moby-Dick itself that makes the book such a satisfying literary reflection. He writes:

Just as every whaleman in the novel has his own unique notion regarding Moby Dick the whale, every reader has his or her own unique understanding of Moby-Dick the book. As Ishmael might say, it “begins to assume different aspects, according to your point of view.” To insist that any particular reading of the novel is somehow truer, or more worthwhile, than all others is to fall into the same trap as Captain Ahab.

In true Zen spirit, Herman saves this insight from its potential for nihilism by the care he takes over details, individual and concrete. His discussion progresses by loosely following the trajectory of the novel—focusing first on Ishmael and his “way-seeking mind,” then on the white whale as the figure for the absolute or ultimate unknowable, and finally on Ahab and his obsession as a self-consciousness that even in its suffering must cling to its sense of separation.

From the first words of the novel—the famous “Call me Ishmael”—Herman brings his literary reflections and his dharma reflections into conversation with one another, and his approach here at the beginning can stand as example for the whole. Playing off those first words of the narrator, Herman writes: “Call me, he says, as I begin this new life, with this new name. It is at once an embrace of his own existence and a plea for us to join him. Call me—establishing the reader’s essential role in his narrative. Call me—I cannot exist without your call. Call me.” He continues:

From the first words of the novel—the famous “Call me Ishmael”—Herman brings his literary reflections and his dharma reflections into conversation with one another, and his approach here at the beginning can stand as example for the whole. Playing off those first words of the narrator, Herman writes: “Call me, he says, as I begin this new life, with this new name. It is at once an embrace of his own existence and a plea for us to join him. Call me—establishing the reader’s essential role in his narrative. Call me—I cannot exist without your call. Call me.” He continues:

[T]hat Ishmael requires us to join him on his cetological meditation suggests that he would be unable to attain knowledge of the whale without his reader participating in his effort. This recalls Dogen Zenji’s teaching (originally from the second chapter of the Lotus Sutra, “Preaching”) that “buddhas alone, together with other buddhas, are directly able to realize [truth].” It is only through appealing to an outside source that one can “affirm that he understands clearly and fully.”

In a further reflection on the opening words, Herman tells us that the name Ishmael “is often translated as ‘God hears.’ So we might read this sentence as ‘Call me “God hears.”’ Or perhaps it should be ‘Call me the one who God hears’ or ‘Call me the one who God has heard.’”

Herman relates this “Call me” to the standard sutra opening “Thus have I heard” (and could as easily, I think, have taken us in another direction as well, to some similar imaginative riffing on the Bodhisattva Regarder of the Cries of the World, for surely this Ishmael whose name means “God hears” can be read as the novel’s cry regarder, its Kanzeon).

As Herman’s reading continues, giving in this way his close attention to the imagery, language, and idea within the world made by the novel, he brings to bear mutually illuminating images, language, and ideas from the teaching and practice of Zen. If Melville’s language likens the whaling ship to a monastery and its men to monastics, Herman’s own experience of monastic life enlivens his reading of the metaphor. If men at the watch go drifty, there are parallels to be found in meditation. Herman writes:

When Ishmael succumbs to a “dreamy mood losing all consciousness,” he describes the progression of his mental states in precise and astute detail… He strikes a stable balance between seeking the whale but not grasping the whale—between whaling and not-whaling (we might call it “non-whaling”)—leading to his realization that there is ultimately no sperm whale to be found.

And if Ishmael’s transformation and ultimate survival may to a technically minded reader seem mere narrative necessity, to the Zen practitioner they embody and enact the movements on a path of practice.

Throughout Zen and the White Whale, Ishmael, the whale, and Captain Ahab receive equally close attention, with engaging and thoughtful side visits to the other whalemen, and Zen is spoken here in the voices not only of Dogen but also of Dongshan, Linji, Suzuki Roshi, and Tenshin Reb Anderson, among many others.

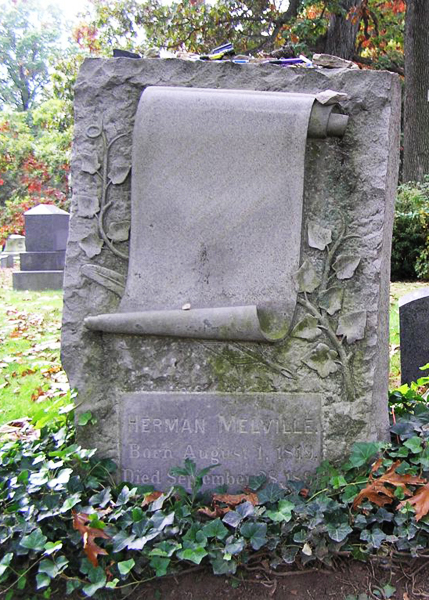

When in his conclusion Herman describes the blank unfurling scroll that adorns Melville’s gravestone, its “blankness” has been established as an image carrying the weightless weight of Moby-Dick and dharma with it. At the end of his acknowledgments, Herman expresses gratitude directly to Melville “for writing this strange book about a whale. It breaks my heart to think you died without knowing what your work would one day mean to the world.”

Thus, all along its way, Daniel Herman’s Zen-based reading serves to bring the great American novel of whalers, whale, and whaling ship out of its classic, 19th-century, masculine-oriented, academic—dare we say even stuffy?—confines into timeless life with all of us here and now, where in truth it has always belonged.

I have to confess that I enjoyed reading Zen and the White Whale so much that at first I found it difficult to write about. More than anything Daniel Herman’s book moves me to go out and get my hands on a copy of Moby-Dick and to read it again. May it have that effect on others, whether students of Zen or students of literature, or most happily both.

__________

Don’t miss Daniel Herman’s reading featuring Zen and the White Whale at City Center on Friday, September 26 beginning at 7:45 pm. A $10 donation is suggested, though no one is turned away for lack of funds.

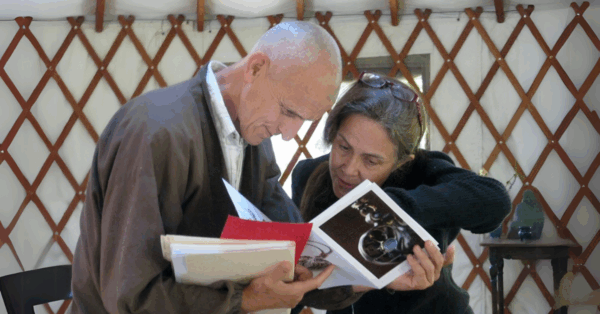

Catherine Gammon is a fiction writer and Soto Zen priest ordained by Tenshin Reb Anderson in 2005. She lived at Green Gulch and Tassajara from 2000 through 2010, served as shuso at Green Gulch in 2010, and returns to residence periodically. Her novel Sorrow (Braddock Avenue Books, 2013) was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award. For more information, visit her website.

(Photo credit: headstone by Anthony22 at en.wikipedia)