The procession, presenting several ceremonial objects at the altar, such as Steve’s robes, bowls, staff and other items. His ashes were carried in around the neck of Linda Ruth Cutts, as shown here.

(All ceremony photos by Shundo David Haye.)

The funeral ceremony for Abbot Steve was held at Green Gulch Farm Zen Center on Sunday, February 9, at 3 pm. The two-hour ceremony was live streamed on the web and projected on screens for the overflow seating in Cloud Hall at Green Gulch and in the dining room at City Center—all while a steady downpour refreshed the land amid one of the most severe regional droughts on record. A reception afterward filled both the Green Gulch dining room and the Wheelwright Center. This post offers some records from the day honoring the memory of Myogen:

- Program listing

- Photo collage of Steve, plus song lyrics (“Incredible Machine”)

- Statement by Steve’s son James

- Condolence statements (PDF)

- Video of ceremony

Program

Obonsho – sounding of the Great Bell in memoriam

Densho – calling of sangha to the ceremony

Procession with ceremonial objects

Dharma words, incense offering

Chanting the Ten Names of Buddha

Offerings of dharma words, sweet water and tea

Great Flame Mudra

Chanting the Harmony of Difference and Equality

Statements from invited speakers representing family, friends and sangha:

Lane Olson (wife)

Nathan Stucky (brother)

James Asher (son)

Susan O’Connell, San Francisco Zen Center (President)

Michael Stusser, Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary

Chikudo Lew Richmond, Vimala Sangha

Jakugan Tom Millard, Dharma Eye Zen Center

Daito Steve Weintraub, Old Zen Guys

Invited teachers (from left) Ryushin Paul Haller, Kiku Christina Lehnherr and Dairyu Michael Wenger.

Chanting the Dai Hi Shin Dharani

Incense offering by family, procession members, and invited teachers

Dedication & chanting of All Buddhas

Recession

Program Insert

View this PDF of the program insert for a photo collage of Steve, as well as the lyrics to “Incredible Machine,” which Lane sang a cappella (subsequently a recording by the original band was played over the sound system).

Statement from James Asher

One of the most moving parts of the ceremony was the statement given by Steve’s son, James Asher, which is reproduced below.

I’ve been trying to make sense of the empty space that’s been left by my father’s loss, and honestly I’m not sure I’ve been doing that well at it. There seems to be a vacant lot now where before there was something big and beautiful. It was there every day as a kid as I walked by. And now there’s just emptiness. And despite the significance of this emptiness to even a Jack Buddhist like myself I still think there ought to be something there. But there isn’t—not even any words. Mostly all I can see there when I try to make meaning is an image of my father’s smile, so I’d like to speak to this for just a minute.

My father had a wonderful smile. And in his final days we got to see a lot of it. Indeed three hours before he passed I was able to sit by him in his dying process—to witness, to be present and just to tell him softly that I loved him. He would slowly open his eyes and smile a loving, peaceful smile and whisper the same to me. This was not the smile of an opiate induced stupor but of one who was present and fully accepting. This was the smile of one who had made peace with the pain he was in—the pain of his cells shutting off—and one whose arms were opened to death with a welcome smile on his face. A smile, it’s important to note, that I watched him CHOOSE in the middle of his wracking pain. His mouth slowly and deliberately forming the gesture, holding the pain, wrapping it in a smile until even the pain itself was humbled by the beauty of such acceptance.

When I finally walked away from my father’s bed that night he died I turned and looked back through the crack in the door one last time to see him resting with the same beautiful smile on his face. A few hours later at four in the morning Patrick, a large hospice nurse big enough to carry my father if need be, was sitting quietly watching my father as he slept. He said he noticed Steve’s breathing become shallow and quick. My father suddenly opened his eyes and looked directly at Patrick. He then leaned forward and held out his hand which Patrick took in his. My father squeezed Patrick’s hand firmly, looked him in the eyes and smiled. And then laid his head back down, closed his eyes and stopped breathing—a smile still on his face. If there is testament to a life well lived surely it is this.

From left: Hannah Dominguez (daughter) and students Elizabeth Sawyer, Natalie Davidson, and Renshin Bunce.

And he stood up for me, came to my soccer games and cheered for me up and down the sidelines even when I swore to my team mates that I didn’t know who the crazy gesticulating guy in the black robes and shaved head was—he still came to those games, every season—the simple things that don’t go unnoticed by a child over the years. He showed up. He protected and guided my sisters and I and he accepted the pain that comes with being a father. The inevitable heartbreaks of parenting. The pain of enduring your own children’s mockery. For instance if on a rare occasion he would get upset with me I might find that a perfect opportunity to ask him if Dogen would get so upset? “Yes I’m 14 and I didn’t come home til 5 am last night but why live in the past when we can live in the now. Let’s just hold space for the present moment Steve, mmkay?” And he would! And tell me very calmly that I was grounded—holding space all the while.

As a young boy I watched with horror as he accidentally shoved a drill press all the way through his thumb nail to which he responded with signature detachment, “oh wow look at that, its gone all the way through my thumb—oh boy that smarts.” He famously would forgo Novocain when getting fillings at the dentist. Why? I pleaded. It hurts me just to think about—please get the Novocain—not for you but for me! But no, he said it was far more annoying to have a numb mouth for four hours than to sit with the pain for a few moments—to hold space for it.

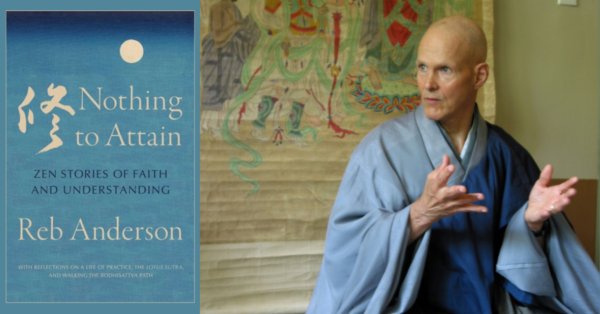

The three doshis for the ceremony were Eijun Linda Cutts, Tenshin Reb Anderson (standing behind), and Sojun Mel Weitsman (not pictured).

And this is how he taught me that one can have a relationship with pain that begins to nurture a space—an emptiness beyond pain, beyond our opinions of pain—to indeed hold space for it. My dad taught me so much about living but perhaps the greatest thing he taught me was to show me how to die. To smile at pain—at death—at the great harmony of the universe that ebbs and flows with every breath. To watch him face dying consciously, smiling and with a surrendered heart has seemed to me the greatest measure of his spiritual path. I had no idea this was actually possible. That one has the option to smile through it all even through the very end. And if one has no fear to meet death with a smile, then what’s to fear in meeting life the same? I guess my father must have known he was teaching even here. His greatest lesson.

Not long before my father died my sister told me over the phone from New York that when our father was a young boy there was a wild horse that lived in the pastures of his childhood farm. At some point Steve had endeavored to tame it but was having no luck. His grandmother, who had been watching him, finally said, “Have you tried just getting on it and riding it?” Well apparently my father had been having dreams about this horse in the last week of his life. He wrote about it in his journal and talked about it with my sister. In his dream he would get on the horse and it would jump the fence of the pasture but then come to a stream that he was afraid to cross over. As our father began slipping away in the last day or two of his life Hannah asked me to tell him to get on that horse and ride. Jump over the water, she said, and ride on. Be free. Tell him we are all fine—don’t be scared, we will all take care of each other. So I did as I sat beside him holding his hand: Ride on Pop. Jump over the water and keep going—just keep on riding brother—Be free.

My father died the day of the turning of the New Year—fittingly The Year of the Horse. He died with a glorious peaceful readiness in his heart. He rode a wild horse over the great threshold and left us with awe and love and a smile to tame even death.

To all of you who have comforted us and each other, know that this is the legacy of spirit that Myogen Steve remains in: to make our living deeper, to redirect us to love in our lives and as much as we can to smile. The simple wordless act of smiling to teach us, to guide us—to begin and to end.

Thank you to all our immediate family and the extended family of the Zen community who have been so loving and supportive in this time. All the love you expressed, all the posting on Facebook, the beautiful stories and memories you’ve shared these past few months? You couldn’t possibly honor Steve any more than by making his children even more proud of their father than they already are. To know he was so loved by his community and that he helped so many of you in this life. Thank you deeply for sharing that and for being a part of this family. Seeing your reflections posted online was a discovery of who my father really was beyond what we knew of him. And it was also a discovery of many more brothers and sisters with the same father—many more relatives with the same brother, the same friend. And therein is the meaning of all this for me. That this empty unnamed space in my head from the loss of my father—that this space that seems to ask me to put something there could be filled with love, I think that would sit very well with my father and I’m sure that it does.

In the vacant lot where once a tower stood—there love has grown as wild grass. The Sun. The Rain. The stars…

In the vacant lot where once a tower stood—there love has grown as wild grass. The Sun. The Rain. The stars…

My gratitude to all of you for helping to make meaning in this confusing, amazing and transformative time. Thank you for reflecting back to us our father, your brother and friend and helping us all walk on this path together. And finally thank you for helping him onto that wild horse to jump over that body of water to the other side bold and graceful with love spurring him on and a smile in his heart. This truly is the way.

Condolences

View a PDF of formal condolence statements from Soto Zen officials as well as others. Although these were not read at the funeral, they are included here for the record.

Video of the Ceremony

This video is recorded also on our live stream site, where some comments may remain from the broadcast.

__________

Ceremony photos by Shundo David Haye

Thank you James for your beautiful eulogy. You are your Father’s son.

Fran and Wayne