I still appreciate Suzuki Roshi saying, “When you are you, Zen is Zen.” He didn’t say when you get to be Zen enough, then you’ll have really gotten somewhere. So much of Suzuki Roshi’s way was to find out what’s appropriate for the occasion and what works for people. —Edward Brown

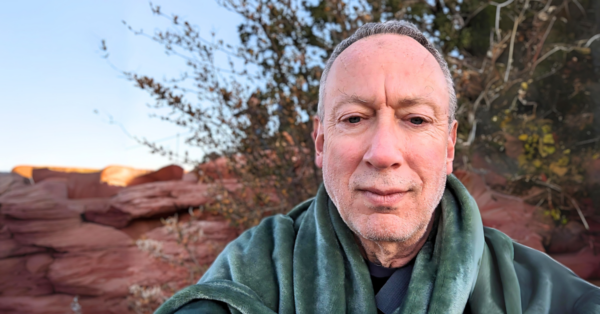

by Catherine Gammon (Photos courtesy of Edward Brown)Â

Edward Espe Brown joined me in the Peace Garden at Green Gulch Farm Zen Center in early November to talk about the Saturday sittings he regularly leads here. A combination of zazen, movement, and dharma teaching, the sittings are suitable for beginners as well as for longtime practitioners. The next Saturday Sitting with Edward Brown will be offered at Green Gulch on December 14.

You’ve been leading these one-day sittings at Green Gulch for something like twenty-five years, and you’ve given them their particular flavor pretty much from the start. How did they come into being? I started offering them when I left Zen Center. Leaving Zen Center after twenty years is probably the most difficult thing I ever did in my life. It’s very difficult to suddenly need to find a place to live, to get a car, to have enough work, to have new friends, to have a new lifestyle—everything is very challenging after twenty years at Zen Center.When I was tanto [head of practice] at Green Gulch in 1985, and in all my time at Zen Center, we had had sittings from five in the morning till nine at night, and when I left I had this thought that I wanted to lead a sitting that was oriented more for lay people who are living a lay life. I decided to offer sittings from nine to five, so that you could have breakfast at home and then dinner back at home or dinner out, and then you weren’t so exhausted. You didn’t miss Friday night because you had to go to bed early to get up early the next day, and you also didn’t miss Sunday because you were so exhausted from sitting from five to nine. Then you actually could have a weekend and a sitting. That was my original idea, to have it fairly short yet still focused.

You’ve been leading these one-day sittings at Green Gulch for something like twenty-five years, and you’ve given them their particular flavor pretty much from the start. How did they come into being? I started offering them when I left Zen Center. Leaving Zen Center after twenty years is probably the most difficult thing I ever did in my life. It’s very difficult to suddenly need to find a place to live, to get a car, to have enough work, to have new friends, to have a new lifestyle—everything is very challenging after twenty years at Zen Center.When I was tanto [head of practice] at Green Gulch in 1985, and in all my time at Zen Center, we had had sittings from five in the morning till nine at night, and when I left I had this thought that I wanted to lead a sitting that was oriented more for lay people who are living a lay life. I decided to offer sittings from nine to five, so that you could have breakfast at home and then dinner back at home or dinner out, and then you weren’t so exhausted. You didn’t miss Friday night because you had to go to bed early to get up early the next day, and you also didn’t miss Sunday because you were so exhausted from sitting from five to nine. Then you actually could have a weekend and a sitting. That was my original idea, to have it fairly short yet still focused.

You offer instruction in forms during these sittings, but not in the way forms are usually offered at Zen Center. Could you speak to the difference? Because most of the students at these sittings are not formal or residential Zen students I don’t emphasize the forms in quite the same way. I always teach the forms, but it’s not like 90 percent of the people sitting are following the forms, and if you’re not, you can just look around and see what to do. In this case you look around and nobody else knows what to do either.

Photo: Valerie Boquet

I teach people shashu, I teach people kinhin, I teach people sitting, I teach people to bow facing the cushion and turn clockwise and bow away and so on, but I’m not making sure everybody’s following this instruction. From my perspective, without a core of people doing the forms, it becomes a little too rule-bound. I often explain that by practicing forms you can come to understand things through your body, through your physical experience, rather than through your thinking. But I don’t say you have to do this. I encourage everyone to try out the forms, but I let people come to their own decision about how much attention they will give to the forms, especially since there’s not a cadre of Zen students already following them.I also allow people to come in late and leave early. I don’t close the doors. I don’t go looking for people if they’re not there—because it’s not an established situation, where people have said they’re committed to doing the schedule and so on. So in that sense I’m trying to present Zen in a non-coercive way. I’m interested in presenting Zen in a way that makes zazen accessible to people. That was also one of my ideas right from the start.These days there are a number of people who come fairly regularly, but there’s not a group of people who come to every sitting. Every month there are probably four or five people that I’ve known and practiced with for five or eight or ten or twenty or thirty years. And that’s pretty nice.

You offer movement practices with the sittings. Can you talk about the different practices and how the offerings have changed over time? From the beginning I wanted to have a day of sitting that was not just sitting—to include a movement practice, so that people would have a chance to stretch, so to speak, to do some physical movement that would be refreshing and energizing. When the sittings started I was partners with Patricia Sullivan, and she would come with me and offer yoga, and later I invited her student Letitia Bartlett to lead yoga. Over the last few years I’ve often offered some Qigong. People who are really experienced say, “That’s not Qigong.†So I say, fair enough, let’s just call it Ed Gong. What I’m sharing seems to work for people—they can follow along and not need much explanation to do a form or a sequence, just very simple things that help them feel energized and pretty happy and grounded and stable and tall

—That sounds great!

Yes, it’s pretty sweet, and often at the end of it when I say to people just feel your body, they start to notice that they can’t find the outlines of their body in the usual way, and often at that point the sounds start to feel like they’re coming from the inside. I find it a very useful counterpart to sitting. When people aren’t used to sitting they can get pretty tight and pretty stiff pretty quickly just sitting, aside from everything else that’s happening. So from the beginning I’ve offered various combinations of yoga, restorative yoga, and Qigong.I also teach Vipassana outdoor walking meditation, where you practice noting—lift, step, place in conjunction with your walking—and I mention that this can also be adapted for sitting meditation, noting, in and out. It gives you a focus rather than just shikantaza, seeing what happens. It gives you a way to focus in your sitting, rather than just following your breath, or counting your breath. I tell people that’s an option of course, and how to do it. Suzuki Roshi taught us counting the breath. But in emphasizing beginners’ mind, he also taught that you should find out for yourself how to practice.

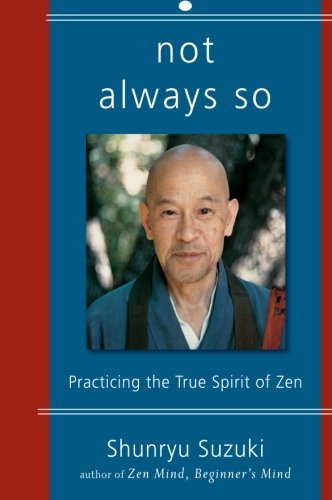

\nSo along with Zen I teach some Vipassana, and I also teach some Thich Nhat Hanh. I tell people they can smile. I remember, back in 1983 I think, when Thich Nhat Hanh visited Green Gulch, and with about ninety people there in the zendo doing kinhin [slow walking meditation], Thich Nhat Hanh spoke into the silence saying, “Some of you are not smiling. You are wasting your time.†And of course this was kind of news to most of us, that there was more to Buddhism than Japanese Zen.There’s a practice called Mindfulness Touch that also has become one of the focuses I use in sitting and walking and Qigong. It’s a practice about learning how to touch and receive information rather than giving out directives, putting more of an emphasis on sensory awareness, sensory awakening, rather than on giving instructions to your body and mind telling them how to behave and what to do and what not to do, as though if you told your body and mind how to behave and how not to behave, your body and mind would just follow along. That would be what Katagiri Roshi meant when he used to say, “Zen is not like training your dog—sit, heel, fetch—Zen is about waking up.†And waking up is to let things come forward and enlighten themselves rather than I’m going to tell them how to behave so that they look like they’re enlightened.  Not Always So, a book of Suzuki Roshi lectures edited by Edward Brown

Not Always So, a book of Suzuki Roshi lectures edited by Edward Brown

You give dharma teaching during your sittings as well. I’ve seen you encircled by students in the dining room after lunch or out here in the garden. Do you give a formal talk or are there other times during the day that you offer teachings? At the end of the first sitting, I offer two readings, and one of them is always a quote from one of the Suzuki Roshi lectures in Not Always So. Along with this passage I usually share a poem: something from Rumi, Kabir, Hafiz, William Stafford, Mary Oliver. I find the written passages so powerful, and they can penetrate deeply if I share them while people are sitting. And then throughout the day, I offer a lot of talk along with the sitting meditation, walking meditation, and movement. Especially for newer students, I think this talk is useful to orient them to the spirit of practice, not just the rules and requirements. But I also feel that experienced students can benefit from having a fresh look at the world of practice.So I think what I’m doing is very accessible to the public, and inviting and welcoming because it’s a little less intimidating than a zendo full of people in robes and oh my god they have so many forms here and how does anybody do this and I’m sure I can’t do it right. It can be pretty intimidating for people. So I tell people who come to my sittings, yes, that’s okay, but Zen is actually—you might be surprised to find out—very free. Zen people don’t tell you what to do with your mind in sitting, whether you call it “think not thinking,†or letting your experience come from beyond, or something else.Every so often I hear something like, “Oh Ed Brown, he’s a good teacher for beginners.†And it’s kind of ironic, because in some ways I don’t know that I’m so good for beginners because I’m more interested in telling people the spirit of practice than the letter of practice, and oftentimes new people would do better getting really specific instructions rather than just the spirit of things. So I’m not sure that that’s true, but there’s a view like that, which is similar to the view of somebody who told me, “What you do is very nice, Ed, but you know it’s not Zen.â€

One of the things people always seems to appreciate in your teaching is the admission of the darkness and the difficulty. Your own experience comes through as you teach, and it’s very clear that there is this human life that we live and we struggle with it, and there’s a path but it doesn’t take us out of the struggle, or make us not human. And maybe that’s helpful for beginners, but I especially think for people who have practiced for a longer time that’s a great thing to be reminded and reassured about. In that vein I still appreciate Suzuki Roshi saying, “When you are you, Zen is Zen.†He didn’t say when you get to be Zen enough, then you’ll have really gotten somewhere.So much of Suzuki Roshi’s way was to find out what’s appropriate for the occasion and what works for people.You know, I’m a student of Suzuki Roshi’s, I’m a disciple of Suzuki Roshi’s, I do the best I can at being his disciple, his heir so to speak, and sharing something about his spirit and his practice with people. He said at one point, “All I can teach you is what I learned, the practice I learned as I learned it in Japan, that’s what I can teach you, and in the future here in America you will have to decide, find out for yourself, what you want to teach and how you want to teach Zen.†And so I took his word for it.__________

One of the things people always seems to appreciate in your teaching is the admission of the darkness and the difficulty. Your own experience comes through as you teach, and it’s very clear that there is this human life that we live and we struggle with it, and there’s a path but it doesn’t take us out of the struggle, or make us not human. And maybe that’s helpful for beginners, but I especially think for people who have practiced for a longer time that’s a great thing to be reminded and reassured about. In that vein I still appreciate Suzuki Roshi saying, “When you are you, Zen is Zen.†He didn’t say when you get to be Zen enough, then you’ll have really gotten somewhere.So much of Suzuki Roshi’s way was to find out what’s appropriate for the occasion and what works for people.You know, I’m a student of Suzuki Roshi’s, I’m a disciple of Suzuki Roshi’s, I do the best I can at being his disciple, his heir so to speak, and sharing something about his spirit and his practice with people. He said at one point, “All I can teach you is what I learned, the practice I learned as I learned it in Japan, that’s what I can teach you, and in the future here in America you will have to decide, find out for yourself, what you want to teach and how you want to teach Zen.†And so I took his word for it.__________

Visit our website for scheduled Saturday Sittings with Edward Brown, including the next one, on December 14.Edward Brown has been practicing Zen since 1965. Ordained as a priest by Suzuki Roshi in 1971, he received dharma transmission from Mel Weitsman in 1996. He is the author of several books and also has edited a book of Suzuki Roshi lectures, Not Always So. Ed is the founder and teacher of the Peaceful Sea Sangha.Catherine Gammon is a fiction writer, writing teacher and Soto Zen priest (ordained by Tenshin Reb Anderson), and currently a resident on staff at Green Gulch Farm.

Visit our website for scheduled Saturday Sittings with Edward Brown, including the next one, on December 14.Edward Brown has been practicing Zen since 1965. Ordained as a priest by Suzuki Roshi in 1971, he received dharma transmission from Mel Weitsman in 1996. He is the author of several books and also has edited a book of Suzuki Roshi lectures, Not Always So. Ed is the founder and teacher of the Peaceful Sea Sangha.Catherine Gammon is a fiction writer, writing teacher and Soto Zen priest (ordained by Tenshin Reb Anderson), and currently a resident on staff at Green Gulch Farm.