by Sachico Ohanks, Communications Coordinator at SFZC

In May, Central Abbot Myōgen Steve Stücky and naturalist Steven Harper will pair up to lead The Nature of Zen, a four-day retreat that combines Zen meditation practice with exploring the Ventana wilderness. This retreat has not only become an annual tradition at Tassajara, but it harks back to the longstanding Zen and Taoist tradition of appreciating nature, the source of our existence.

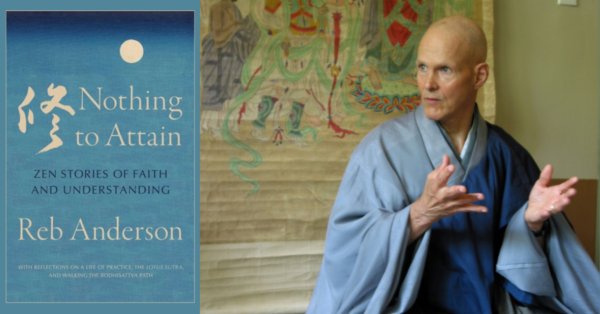

photo by Dan Quinn

I had the opportunity to talk with Abbot Steve this week in his City Center office about the upcoming retreat:

Sachico: How do you and Steven Harper weave together Zen practice and exploring nature?

Abbot Steve: It’s great working with Steven because of his own sense of Zen practice, and his being subtly tuned into the natural world. It’s also a great time of year. We plan the retreat early in the year before it gets to be too hot. Usually there are many wild flowers blooming, so it is just a beautiful time to be hiking. We do several hikes. Usually, we hike to the Wind Caves, we do the Horse Pasture trail, and then another shorter hike.

We do zazen. I actually teach zazen. Sometimes there are people who have never sat zazen before, so I go over basic instructions, answer questions and look to see that people are actually finding some comfortable way to sit. I do that each day.

We also extend that into a walking meditation practice, so the hikes are a chance to be mostly silent and open up all the senses to what we are experiencing, noticing what the mind tends to do and how it tries to add layers of languaging. Naming things actually takes you out of the present moment. Silence brings present moment awareness to the hike. It’s a seamless transition from zazen practice into walking.

We clearly mark the threshold of entering the wilderness, so that people are aware of the transition. Fortunately Tassajara is surrounded by wilderness, the Ventana wilderness, so to actually go out from camp into the wilderness is a practice of respecting our source of existence. Our existence is dependent on the wild world, and we often forget it because we operate so much with an orientation towards the civilized world that is all constructed by human beings. But the world constructed by human beings is completely dependent upon and interdependent with the wild.

Sachico: How is experiencing nature relevant to Zen practice?

Abbot Steve: When we talk about the natural world, in this case Zen and nature, I would say we are particularly aware of the mountains, the earth, and rocks; and particularly aware of the fragrance of the air; particularly aware of water; particularly aware of all the plants in our environment and how we share one body. We experience our own body as not separate from the body of the mountain and the body of the trees, the birds, and so forth. It’s one thing to say that and it’s another to actually experience non-separation with all the senses.

I think it also harks back to Zen evolving in China at the intersection of Chinese culture with Buddhism coming from India. In Chinese culture, particularly the Taoist aspect of Chinese culture, there was a lot of respect and appreciation for, and a tremendous depth of wisdom about, the energetic forces of the natural world. The language of Taoism influenced the language of Zen. In many cases, Zen Buddhism borrowed terminology from Taoism – like the word way, Zen way or Buddha way is Tao. The word Tao was adopted to refer to the path of Dharma, the path of Practice.

Much of Zen writing points to the natural world. Dogen does this in many ways, but particularly with his essay Mountains and Rivers Sutra. On the retreat I sometimes use the Mountains and Rivers Sutra and other times I use haiku that point to nature. Haiku are usually seasonal and often evocative of the transiency, the impermanence of life, and the uniqueness of this moment of encountering something in the natural world. As part of this retreat, I often ask people to write a little haiku. Poetry is a part of this. We will go out some place, stop, and write a short poem.

photo by Ben Guevara

Sachico: I understand that Suzuki Roshi had a particular fondness for rocks.

Abbot Steve: Suzuki Roshi loved rocks, and there are lots of rocks and boulders at Tassajara. In his free time, he liked to engage in moving the rocks around and building the little rock garden by the abbot’s cabin. So that’s an area where we preserve the rock placement that he did.

He would go into the creeks and find rocks that he liked. Some of them are pretty big. If you walk up to his memorial site or ashes site, there is a rock that is basically a stupa for him. And that rock is a rock that he picked out when he was looking for rocks with Dan Welch. Dan told me this story. They were just going up the creek and looking for rocks, and Suzuki Roshi said this is really a wonderful rock. It was partly visible and partly hidden under ground. He said, this would make a good rock for someone’s memorial stone. At the time, he wasn’t referring to himself. However Dan remembered it. So after Suzuki Roshi died, Dan went back and found that rock and dug it out. It is a big rock. You’ll see when you are up at the memorial site.

Suzuki Roshi really liked the ruggedness of the mountains. I think he honored this tradition of Buddhism being nourished by nature, and the story of Buddha himself going to sit in the jungle. The Zen masters in China were associated with mountains. Often their Zen name would be their mountain name. Suzuki Roshi really had a deep, heartfelt understanding of nature and of Zen not being separate from that understanding.

photo by Shundo David Haye

The Nature in Zen retreat is from May 2 – 5, Thursday through Sunday. The retreat will feature daily zazen and moderate hiking along the trails of Tassajara. The co-leaders emphasize safety and are careful to give retreatants the information they need to hike safely in the wild. “We take care to take care of the people,” says Abbot Steve.

Steven Harper is a wilderness guide who has been led expeditions for over 35 years and studied Buddhism for over 25 years. Central Abbot Myōgen Steve Stücky has been practicing Zen since 1971 and received dharma transmission from Sojun Mel Weitsman in 1993.