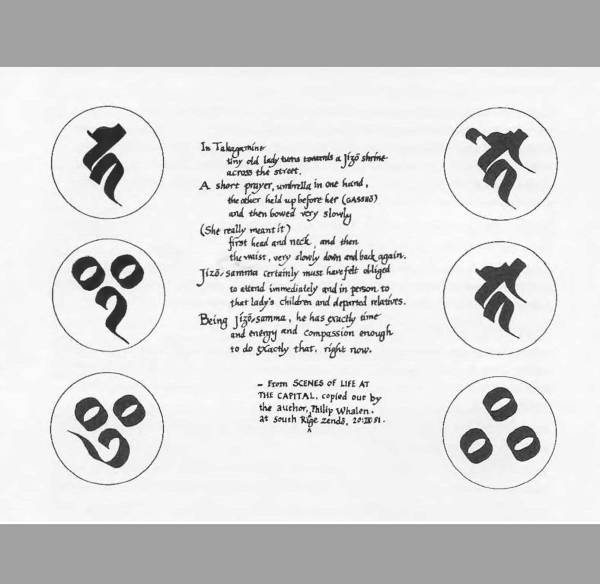

Last week, David Schneider came to City Center to read from his new book about a former City Center resident, Beat poet Philip Whalen. Here is a picture – and a transcript – of a broadside that Philip created in 1981, bordered by six “Siddham” letters drawn by David Schneider.

In Takagamine,

tiny old lady turns towards a Jizo shrine

across the street.

A short prayer, umbrella in one hand,

the other held up before her (gassho)

and then bowed very slowly

(She really meant it)

first head and neck, and then

the waist, very slowly down and back again.

Jizo-samma certainly must have felt obliged

to attend immediately and in person to

that lady’s children and departed relatives.

Being Jizo-samma, he has exactly time

and energy and compassion enough

to do exactly that, right now.

∼ from SCENES of LIFE AT

THE CAPITAL, copied out by

the author, Philip Whalen,

at South Ri(d)ge Zendo, 20: IX : 81.

The Jizo statue in the zendo at Green Gulch Farm. Photo: Shundo David Haye

The broadside was created by Philip Whalen as a fundraiser to help pay for the Jizo statue in the zendo at Green Gulch Farm, right. Jizo’s staff has six rings that symbolize the six realms of existence: in ascending order, hells, hungry ghosts, animals, bellicose demons, humans, and heavenly beings.

The six “Siddham” syllables on the broadside are by David Schneider, and he tells us that they portray Jizo in all six realms.

A copy of Philip Whalen’s Jizo broadside can be seen in the Wheelwright Center at Green Gulch Farm.

David Schneider explains the Siddham syllables

In every culture in which it appeared, writing has been considered something magical. Letters and characters have been used to form words and sentences, to do business, to govern, to conduct love affairs – in short, to communicate meaning to other human beings. But letters have also been thought to have the power to communicate with unseen energies and beings, and to contain in their very shapes, and in the act of writing them, the kernel of these energies. This was true of Hebrew letters, Greek, and then Roman letters – all these alphabets have esoteric meanings as well as their usual significance – and it was certainly true of Sanskrit, where the very name of the principle alphabet – Devanagari – means “gift from the city of the gods.”

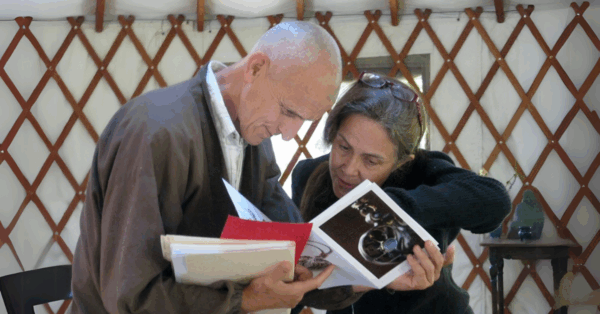

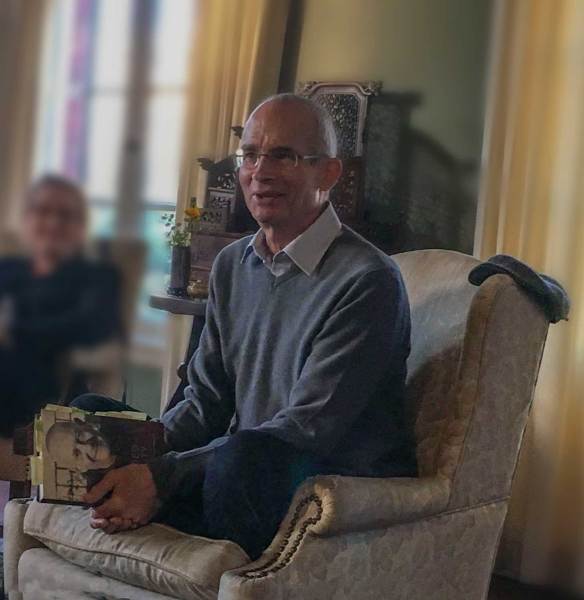

David Schneider reading in the dining room at City Center on June 3. Photo: Steve Silberman

The letters written here are in the Siddham script, an ancient writing system, parallel to Devanagari. “Siddham” means “perfected” and the letters were used chiefly for writing religious texts: short sutras, dharanis, mantras, and seed syllables; this seems to have been especially true during the period from the 5th to the 8th centuries AD, when Chinese pilgrims began arriving in the great Indian Buddhist universities. This same period saw the rise of tantric, or esoteric, Buddhism, in which many of the meditations incorporate the use of seed syllables.

The idea that a written or spoken word could allude to, invoke, or contain the essence of an energy – or for that matter, a particular Buddha or bodhisattva – was not difficult for a literate Chinese person, given the pictographic nature of Chinese writing. Siddham was taken back to China and propagated there by tantric adepts, the renowned Amoghavajra principal among them.

As a mystical system of writing, Siddham came into full flower in the 9th and 10th centuries in Japan, in the Tendai, and especially in the Shingon schools of esoteric (or tantric) Buddhism. Here, entire pantheons of Buddhas and their spiritual families would be elaborately arranged in mandalas, represented only by bija (seed syllables) instead of more graphic painted portraits. The letters on display here follow models written by the greatest of the Shingon calligraphers, Chozen and Yuzan.

Crowded by Beauty: The Life and Zen of Poet Philip Whalen, David Schneider, University of California Press, 2015.