By Tova Green

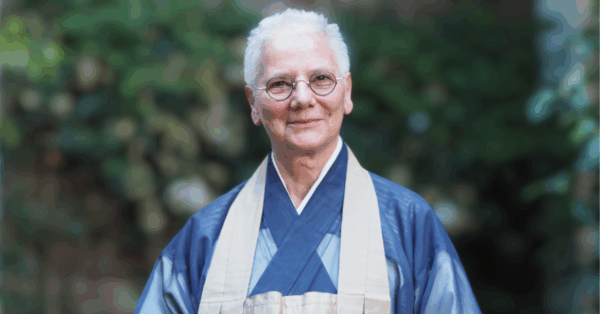

From May 9 to June 3, Chimyo Atkinson will be leading Be Nothing: Understanding Impermanence and Finding Liberation, an intensive practice period with both residential and online participation options.

Her texts will mainly be the Buddha’s first teaching on the Four Noble Truths and Eihei Dogen’s Genjo Koan. Buddha’s first teaching is about suffering, and the cause and end of suffering. “We know it’s the ego and delusion that‘s causing all the suffering. It’s hard to remember that. There’s a build-up of stories and identities we are attached to and have to constantly drop.”

Chimyo had a glimpse of this on a mountain in Japan. She didn’t have a passport until she was forty-two. The trip to Japan was the first time she had been out of the United States. “I was a Black woman in this strange land. I had put myself in a certain box based on ideas I grew up with, ideas imposed upon me—ideas my self-limiting mind makes—and so for a moment at least I was exactly who I was. I felt a sense of liberation for that split second, as if I had dropped away body and mind. We’re so attached to our creations. It’s not a matter of wanting to be something. It’s about allowing ourselves to be, with no prediction of what that can be. I want to remove those limits. That’s what the Buddha is telling us to do. This leads to the eightfold path, beginning with right intention and right view, etc. We have to drop all the illusions. I don’t claim to understand the Genjo Koan, but a lot of it speaks to me. In my opinion, there’s no other teaching. Everything else is just that, trying to explain/analyze the first teaching.”

Chimyo uses the word “liberation” rather than “enlightenment.” She sees enlightenment as connoting knowledge, rather than a state of being. “Liberation is a magical, all-knowing, all-seeing connection. We’re always talking about how we treat each other—liberation from oppressors and liberation from the self that in delusion seeks to oppress.”

During the intensive, Chimyo hopes to hear from the voices of participants; she is stimulated by that. She tries to find clarity with other people. “There is no end to learning and developing in Zen practice—and there’s no way to learn unless there is interchange with others, feedback given in a kindly way, helping one another.”

Chimyo sees monastic training as a very important component of priest training. “The container you have in the monastery is a real crucible. It showed me a lot—it forced me to look at myself and my intention, my behavior, to deal with my own resistance, ego, and excuses with a group of people who were doing the same thing as me, who were not my blood, not my friends. In the monastery I had no choice about what to eat, what to wear, when to go to bed. When that’s taken away I could see what’s really important. For three months I couldn’t go home. I had to deal with the person who was difficult for me. It doesn’t mean you become friends but a certain love develops, a real understanding of another person who is just as tender as I am, who has good and bad qualities, just like I have.”

Most of Chimyo’s monastic practice took place at Great Tree Zen Women’s Temple near Asheville, NC. She also did three angos (three-month periods of intensive practice ) in Japan, including one at Aichi Senmon Nisodo (women’s place of practice) in Nagoya. The ango at the Nisodo was much tougher than those that catered to westerners and offered lots of breaks, treats, and study time.

At the Nisodo, the schedule was monastic—getting up at 4 am for zazen, with one activity after another all day long. “The bell rings and you move to the next thing.” Chimyo’s whole day was basically focused on caring for the community, cooking and cleaning. She tried to be as compassionate as possible in a difficult situation—34 women living together in close quarters. She had to face her resistance to caring for people she couldn’t talk to, as she spoke English and the nuns spoke Japanese.

That experience fed her question: “How do I walk the eightfold path with this deluded mind? I have to get past it, drop it. The forms—what you do in a certain room, don’t mean anything. The deeper teaching is what you’re doing it for.”

Chimyo’s Dharma name, which means Shining Wisdom, was given to her by Rev. Teijo Munnich, the founding and guiding teacher of Great Tree Zen Women’s Temple. Chimyo was ordained in 2007 and received Dharma transmission from Teijo in 2015.

You can register for Chimyo’s Intensive Be Nothing: Understanding Impermanence and Finding Liberation for residential or online/visitor participation through May 1.