The gate at Minnesota Zen Meditation Center and Kilian Clark. Photos by Wendy Lewis.

By Wendy Lewis (photos are also by Wendy)

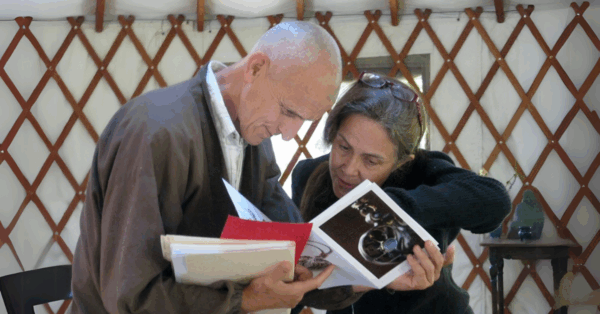

In June 2022, I visited St. Paul and Minneapolis. My visit had been prompted by an invitation from Kilian Clark to visit and give a talk at Minnesota Zen Meditation Center (MZMC), where he is now continuing his practice. Kilian and I had known each other at City Center and, after the death of his teacher Shokan Jordan Thorn, have been meeting in person while he was living in San Francisco and now, since his move to Minneapolis, via Zoom and phone.

Kilian embarked on his Zen practice in 2007. He started attending morning zazen at City Center and soon participated in a beginners’ sitting, one-day sittings, and a practice period. He reread D.T. Suzuki’s writing on Zen and was again “super-inspired” by his teachings and descriptions. Particularly, he was taken by Suzuki’s comment, “If you want to know more, you should find a teacher.”

Shokan Jordan Thorn was the tanto (head of practice) and Kilian participated in a short practice period that Jordan led and started to regularly sit sesshins. During the second one, when the group was sitting facing out during the last period—the lights were low, sounds on the street permeated the atmosphere; traffic, voices—he had a feeling “This is what I’ve been looking for.” During the first few years, he often cried during zazen. “It was bittersweet, about suffering. I was doing something that was going in the right direction.” Jordan asked if he wanted to sew a rakusu and do jukai. “That was fun; a regular meeting, people to sew with.”

Jordan said, “The threads of our life take some time to become clear.” For jukai, Kilian received the name Shinko Jungan / Careful Light, Pure Vow. On the back, Jordan wrote, “Box and lid fit together exactly.” As a carpenter, Kilian works with wood and he related to things fitting together. “Making things work exactly, but sometimes they don’t. That’s part of the struggle.”

He worked as a carpenter with the same company for seventeen years. “There were people before who had been doing this work and people around me who were all doing it. And that was key to my work and practice, that there were people surrounding me all doing the same thing. Not just everybody doing their own thing.”

Kilian moved with his first wife from Minnesota to San Francisco and they stayed together until she graduated from college. Though he wanted to get back with his wife, it was clear that wasn’t going to happen. Jordan helped him through it.

Left to right: Charlie, Kilian, Teddy, and Angie with Cathy Crafton (a former City Center resident who lives in St. Paul) at the Farmer’s Market

Kilian and his current wife Angie dated for a while. Again, Jordan provided a supportive presence and sounding board, and was a part of their marriage ceremony. When their son Charlie was born, Jordan came over to meet him, and Kilian and Charlie visited him often. And then Jordan passed away. Charlie was less than a year old.

Charlie is now five and just started school. Teddy, their second child, is three. After Teddy was born, Kilian and Angie decided to move to Minneapolis to be closer to their extended families.

One evening during my stay, I visited Kilian and his family at home. We took a walk to Lake Harriet, eating juneberries and mulberries along the way. As we picked the juneberries, I passed some down to Teddy. The boys were on their push-bikes. The route we took was a loop down to and along the lake and then back through a rose garden. Angie and I compared notes on our world travels. When we got back, Kilian and I cooked dinner.

Kilian has a carpentry shop and started his own business. As he was working through the websites of the Minnesota Secretary of State, he needed to supply a name. He decided on Shokan, Jordan’s Dharma name; Shokan Timber Framing.

Kilian had participated in an apprenticeship with Paul Discoe at Tassajara, working on the gate there and was introduced to Japanese joinery. “That is like Buddhism and carpentry combined. It’s not like you just buy a tool and start using it. You’ve got to make it work for you. I thought I knew how to put stuff together. But with this, you first put it together in your mind and when you do it, you just do it. It feels very basic, very ancient, very deep. People have been doing this for centuries; that connection to your work, the past.”

MZMC entrance to zendo with maple timbers

Kilian has worked on a few projects for the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center. He spoke with Ted O’Toole, the current head teacher there, and with Rick Okata, the architect for the remodel they were doing when he arrived. There was a large maple tree that had to be removed. Kilian cut the trunk into timber pieces that now outline the entrance to the new zendo. He also designed and built a gate.

“My dad’s neighbor had some silver maples that he had to cut down. I asked him what he was going to do with them and if I could take some. And he said, ‘Yeah.’” Kilian wanted to use them as posts mounted on stones and he incorporated that into the design for the gate. After preparing the foundation for the gate, there were two work days at MZMC, with zazen and kinhin in the morning, and two work periods with a break at lunch. There were 10 – 12 people each day. And they did it.

Now they’re planning to build a machiai—traditionally a waiting structure outside a tea house—which will also have some storage space, in the backyard of MZMC. They have the wood for it, including some cherry logs Kilian “rescued”: “I saw them and couldn’t let them go to the chipper.” He wants to get a workshop together to build the machiai.

Kilian’s connection to San Francisco Zen Center endures. On his altar, there’s a photo of his 2009 jukai group in the City Center courtyard; he sees it and thinks, “‘That’s home.’ That’s the feeling I have for that place. I still feel like I’m connected. It’s a part of me.” There are people here who remember and think of him, too.

Detail of the MZMC gate