By Tova Green

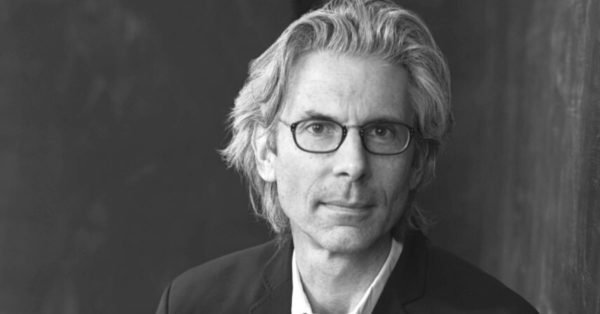

The subtitle of Mark Epstein’s newest book, The Zen of Therapy: Uncovering a Hidden Kindness in Life, captures the essence of his exploration of the relationship between psychotherapy and Buddhist practice, a topic he has been investigating for several decades.

Epstein has been a student of Buddhism since his college days, when he traveled to India, met the Dalai Lama and was exposed to Tibetan Buddhism. Back in the States, he visited Naropa, where he met “the Vipassana crowd,” the young founders of the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre, Massachusetts—Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, and Sharon Salzberg. Subsequently, he attended many retreats at IMS. He admits that he’s “weakest on the Zen front.”

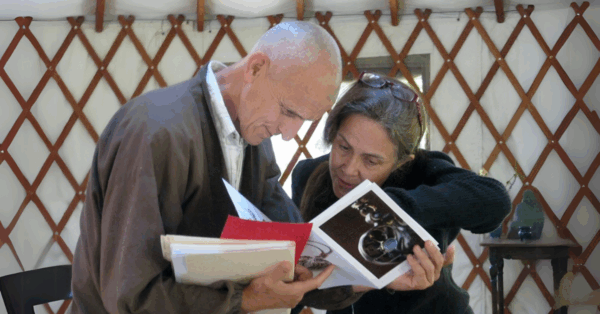

Epstein practices psychotherapy four days a week and devotes one work day to writing. For a year, each week he wrote down the details of one psychotherapy session he had conducted, trying to understand how his Buddhist practice was influencing his work with patients and what he could say about it. Initially he didn’t know these vignettes would become a book.

After a year he looked at what he had written. Each session was like a koan. “The Zen way of thinking permeated my thinking as I worked on the book. What I tried to talk about was the invisible aspect of therapy, transmitted through the relationship, the ‘intangible underlying truth of things.’ The more I looked at the sessions, the more I saw.”

Epstein was introduced to Zen poems while working on the book. The year before, his wife, a sculptor, had created an installation at Madison Square Park in which she included a performance space where there were outdoor events. During a visit to the exhibit, Epstein ran into a friend, Jonathan Cott, who quoted a Zen poem to him, “Under cherry trees there are no strangers” to describe the rapt attention the onlookers were experiencing. This poem stayed in his mind when reading over his therapy sessions. He wrote to Cott asking for more and was sent a list of seven books of Zen poetry. These poems accompanied him as he worked on the book. They came alive for him as never before. “I enjoyed them and could apply them.”

In The Zen of Therapy he writes, “The act of retrieving, recording, and documenting the details of these sessions let me envision every one as a haiku. The minutiae of each ordinary conversation, like the tiny particulars of the natural world that inspired the Zen masters, hinted at larger truths.”

In the book, after describing his path to Buddhist practice and to becoming a psychiatrist, Epstein arranged his interviews with patients chronologically over four seasons. A different aspect of Buddhist teachings is highlighted in each section: clinging, mindfulness, insight, and the transformation of anger. In the final chapter he writes about kindness.

One of the messages he tried to convey to patients is that, “It’s not what you think that is so important, it’s how you relate to your thoughts that matters. We don’t exist as separate beings; we’re relational beings. Psychotherapy is an interpersonal meditation.”

After writing the vignettes for the book, Epstein sent each patient what he had written about them, told them the pseudonyms he had given them and how he had changed things to protect their identities. “Everyone was so generous in allowing me to go forward. They were affirming of the project. Normally I don’t take notes. In an ‘anti-Buddhist way’ I was holding on to the sessions! We all learned from the particularity of the sessions and came back to them in ongoing therapy sessions.”

Epstein hopes The Zen of Therapy will help to preserve what’s worth preserving from the psychoanalytic and therapeutic traditions, and encourage young therapists to explore spiritual traditions. “Buddhism is still entering our culture, and it’s so rich. I’m trying to open it up and show how inspiring it can be.”

The Zen of Therapy is available through the SF Zen Center Online Store.