Interview conducted by Sachico Ohanks, SFZC Communications Coordinator

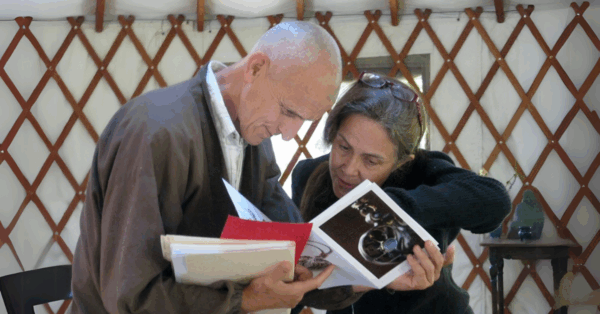

Dr. David Bullard, a licensed psychologist and licensed marital and family therapist, has been practicing individual psychotherapy and couples therapy in San Francisco for over 30 years. A clinical professor at UCSF in both medicine and psychiatry, he acknowledges among his teachers renowned Tibetan-Buddhist scholar Dr. Robert Thurman and poet David Whyte. He co-leads the SFZC workshop Anger and Intimacy: Paths to Healing with Zesho Susan O’Connell, and in this interview he speaks of the struggle and growing that can come from intimate relationships.

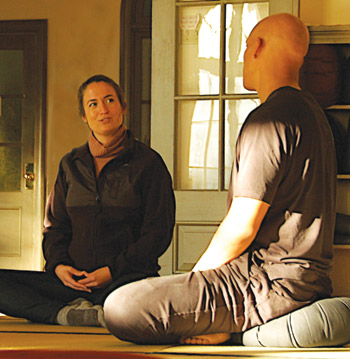

How have Buddhist ideas become useful to you as a couples therapist?

The people we work with teach us.

I was intrigued early on with Alan Watt’s Psychotherapy East and West. My first psychotherapy mentor was the late Dr. Jerry Nims who had been a friend of Watts, and some of that brushed off onto my way of being with the people who came for therapy. Jerry was “mindful” in our meetings long before that had become a popular term. But in addition to what we learn in our coursework and from teachers and supervisors, therapists are a bit like Skinner’s pigeons: we’ve been shaped by the people who come to talk with us about their problems, their sorrows, their anxieties, or when it’s a couple, their couple-unhappiness, as well as about their triumphs and insights. So for years, I’d been working along certain lines that couples taught me that helped them have deeper conversations. For me the term “therapy” sounds too medical—I’m just in a room with two people helping them have deeper conversations with each other.

I had been in private practice about 30 years when in 2005 I went on a trip to Bhutan led by Robert Thurman. Bob spoke from a Tibetan Buddhist perspective that used terminology and words that completely fit what couples had taught me. One of the things that Bob discussed was the notion that there is no absolute self. We all have relative selves. When we understand systemically how one person’s behavior or feelings are impacted by the other person’s behavior or feelings, which are in turn impacted by something that happened to that person the night before, it’s a good way to help them look at what’s going on without blame. Blame is often revealed to be an illusion when you look at it this way.

The other perspective that works for me is to find the truth in the moment in what the other person is saying. For me the truth, in what I hear from someone, is going to be their feeling state at that moment, and that can change a moment later. But in the moment that they’re angry, they’re angry.

People come into couples therapy in two conditions primarily. Some have arguments, often disagree and have a lot of conflict. It can break this cycle for them to learn how to hear the vulnerable, wounded parts and feelings of the other person underneath the anger. Anger, when it’s coming at us, is hard to deal with, but when you hear the softer, vulnerable parts, it’s a lot easier. Other couples come in because they’re feeling distant and they don’t talk. Maybe they’re afraid of having arguments, and there are ways to help each person really listen to the other person’s expressions of feeling without reacting as strongly.

For example, it might be suggested with one person that she has two partners: the partner who’s sitting next to her right this very moment, and the other partner who’s in her head – the conceptual one. She’s upset at him, talking to him, and really dealing with the one in her head much more than with the living, breathing human being next to her who might be feeling quite empathic if she could see him. Part of our work together would be to get to know, in this present moment, who each of them are. The partner in her head may seem to be an accurate representation, in a way, because it’s built on real experiences, but it’s also built on projective distortions, transferences and other influences.

You also speak of using compassion to get past anger.

Exactly. If someone’s angry at me, my first response is usually defensive. I don’t want to be attacked, and I don’t want to be a target of someone’s anger. Their anger will often come out as blame. But if I can breathe and relax and look deeper into their anger, I’ll see their pain. As they say in AA, “Remember, if you are pointing the finger at someone, three fingers are pointing back at you!” To me that just means, I don’t have to hear the blame part, the finger that’s talking about me. I can hear the part that’s true: that person is hurt, or scared, or has some kind of pain in relation to me. And, I want to hear that. I want to hear their feelings, because I care about them.

When my son was five years old, after we visited the zoo, he badly wanted a coke and I said “no,” and I felt good about being a strong dad in saying “no.” He knew how to persist in what he wanted, but I was equally persistent. At the end his feelings escalated and he said, “Dad, you’re a jerk.”

If a parent took that personally, it would be kind of silly. What if I said, “No, it’s not fair to call me a jerk. Your mother and my friends don’t call me a jerk. It’s not true that I am a jerk!”

A parent might instead say, “the name-calling is not okay, because it can hurt someone’s feelings, but I understand you are frustrated and angry because you didn’t get what you want. Grown-ups feel that way sometimes too. I know it’s hard when you’re five and you have no way of getting a coke.” The difference is to hear the truth in what he said, which is not about his father; it’s about him, his feeling state. He’s hurt underneath; he’s frustrated because he didn’t get what he wanted.

What if you see the hurt underneath your partner’s anger, but at the same time are concerned that if you soften and respond with compassion and respect, your efforts won’t be reciprocated?

I think you have pinpointed the crux of the matter. Stephen Covey wrote The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, and I think it’s habit number five: Seek First to Understand, Then to Be Understood. Imagine two human beings talking:

“Please understand me.”

“Please understand me.”

“No, please understand me!”

“Well, you’re not listening to me right now!”

“Well, you don’t hear me, either!”

“Well, you don’t want to hear me!”

“Well, you never did hear me!”

“Well, f—you!”

The way out of that is to first seek to understand. That gets you in a better space. Another idea is, figure out what you want in a relationship, like respect, compassion, caring, understanding. Then give it, just give it.

In relationships you do have to set boundaries. There are abusive relationships, where it’s very important to set boundaries or it may become important to end the relationship. For most of us who are not in abusive relationships, we have to deal with disappointment. I think of it as the First Noble Truth of Relationship: there is suffering in intimacy.

There are wonderful relationships that only suffer a little bit from time to time: You drank all the milk! You didn’t leave any for my coffee! But there’s going to be disappointment at some level, at some point. How we respond to those disappointments is the issue.

It’s important to use Right Speech, and it’s good to aspire to be as good a human being as we can. But all of us fall short of that at some point, and then we’re going to have these disruptions, these problems. That’s when we need ways to talk and reconnect when our nervous system isn’t so inflamed by the fight-or-flight-or-freeze response. One of the ways of setting boundaries when a couple are volatile, with a lot of anger, is for them to have the ability to call a “time out.” At the same time they need to indicate that they’re willing to reengage in the talk in 10 minutes or so. Otherwise, a time out can be used as a way to shut the other person up.

Why do couples, who are in a lot of pain and have been for a long time, persist in trying to heal the relationship?

That’s one of the richly complex, interesting parts of life that comes about from having a relationship. An extreme example would be two people who have a very dysfunctional, abusive relationship, and maybe at some level in their experience in life, they never knew anything else. It’s like if you ask a fish, “What’s it like to be wet?” I don’t think they can tell you.

There is research of John Gottman, who’s done longitudinal studies on couples, which shows that high-conflict couples can be happy and low-conflict couples, conflict-avoidant couples, can be happy. And couples who are a mix of low-conflict and high-conflict can be happy. The key element is not to be a certain way, but to have ways of talking with each other that end up being more respectful and then compassionate.

For most people, if they flare up and show the same patterns of anger and upset, it may be that if they look more deeply into what’s happening, they’ll understand something, in a very profound way, about what they went through as a child—either seeing themselves being treated a certain way or their parents interacting a certain way.

For example, let’s say one woman says that all her life her mother has been really critical of her; she could never live up to her mother’s standards. And we learn that her partner’s issue from childhood is that one of her parents was often absent, and she never got the closeness and connection that she wanted. So now, they find each other as adults, and they’re in a relationship. They’re feeling wonderful in the beginning, the honeymoon phase, and then, little by little, little disappointments come in. The second woman says to the first woman, “You drank all the milk and didn’t leave any for my coffee.” And the first woman, whose mother used to criticize her, feels hurts in the here and now, but it may also reverberate with an old reservoir of pain. She may or may not be conscious of this, and the way she handles being criticized is to shut down and withdraw.

For the second woman, who grew up with a parent who abandoned her and now has an adult partner withdraw from her, it really hits her reservoir of pain of being abandoned. So, she reacts by being even more critical and angry. Some call that a separation protest, the first step of separation anxiety where when we feel disconnected, we might react with anger. Now, what happens to the first woman, when not only is her partner being critical, but now she’s being critical and angry? She’ll withdraw even more. It becomes a negative feedback loop.

When they start to understand and identify those patterns, it leads to deeper compassion for each person. Even more important than “understanding” is when each can experience the other having more compassion for their feelings and also to have more compassion for their own feelings. The most recent work of renowned neuroscientist and psychoanalyst Allan Schore suggests that by expressing and respecting disappointments, all intimate relationships have the built-in capacity for healing old unconscious wounds. These disappointments are inevitable, but can lead to growth for each individual when more deeply empathically shared. The phrase I try to use in my own life, as well as with the people that I work with, is “learn to not take the other person’s feelings personally.” This may sound crazy when you’re in an intimate relationship. Shouldn’t I take his or her feelings personally? No, take them seriously, maybe even in a sacred way, but not personally. Personally means it’s about me. That would be like being reactive when my son Mike called me a jerk. It was not about me; it was about him and his feelings. And, I can respect those feelings.

It sounds like in resolving the problems of an intimate relationship, we can heal in ways that reverberate out to our entire experience of relating.

Yes. Being a couple, or in any relationship with another human being, gives you the opportunity to grow and learn deeper understandings about reality. One reason I enjoy the opportunity to work with couples so much is because I see them experience each other and themselves differently when we get beyond “who is right and who is wrong.” It’s not just that they get along better or talk better, but each individual has a deeper sense of compassion for themselves as well as for the other.

__________

Join David for more on anger and intimacy and the paths he recommends to healing.